Why you should understand the history of a product space

There’s a misconception among many startup founders that a great startup idea is just the premise for a product. They conceptualize their business in a simple, linear way:

Find problem → sell product → make money

In reality, the entrepreneurial journey is more like a maze, with twists and turns caused by variables like competition, technology, and customer feedback. Great startup ideas are a set of many different paths to success and failure. Here’s the Idea Maze from Balaji Srinivasan:

“A good founder doesn’t just have an idea, s/he has a bird’s eye view of the idea maze. Most of the time, end-users only see the solid path through the maze taken by one company. They don’t see the paths not taken by that company and certainly don’t think much about all the dead companies that fell into various pits before reaching the customer. A good founder is thus capable of anticipating which turns lead to treasure and which lead to certain death. A bad founder is just running to the entrance of the maze, without any sense of the history of the industry, the players in the maze, the casualties of the past, and the technologies that are likely to move walls and change assumptions.”

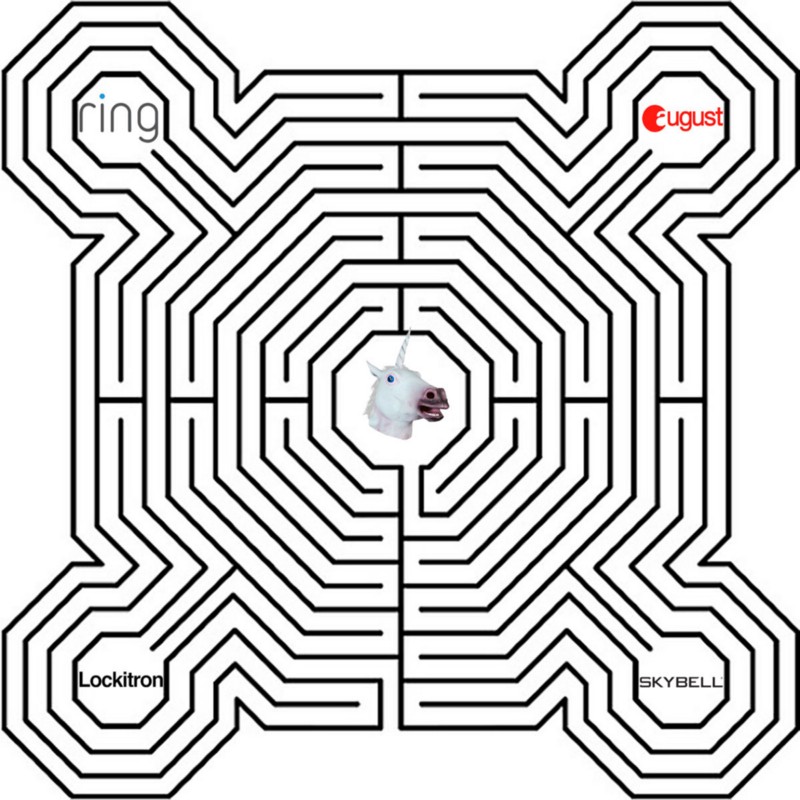

Many startups ran to the entrance of the home access control maze at the same time. Only Ring sold to Amazon for a billion dollars. Some got trapped by manufacturing (Lockitron) or fell into a pit of financing (Otto). Others may have just been out-executed (August, Skybell). In today’s world of hyper-competition, you can be sure that other founders are thinking about your problem space. Who else is running the maze with you? What common pitfalls will they encounter? How will you out-navigate them and get to the other side?

How to map your idea maze

You need a few things to build a good idea maze: a command of business fundamentals, an understanding of changing market conditions, feedback loops with customers, and knowledge of comparable entrepreneurial journeys. Most founders do a decent job with the first three:

- They understand the basics of their business: things like margins, customer acquisition costs, customer lifetime value, and competitive advantage.

- They have a sense of the variables that could affect them over the next few years: changing technology, new competitors, shifting customer demographics, and bad financing environments.

- They know that daily contact with customers yields better businesses. They build customer feedback loops as they iterate on product/market fit.

What founders miss

However, most founders with whom I speak can’t describe the journey of previous companies in their space. They’re trying to run the maze without the collective experience of those that have succeeded or failed before. This may be fine in problem spaces that have quick feedback loops, where you get frequent data on customers or competitors. In domains like hardware, which have long lead times, due to manufacturing or product development, it’s much easier to take a wrong turn and get stuck at a dead end.

To fix this, seek out companies that are analogous to your product idea. Who has a comparable business, acquisition, or distribution model? How did they bring something similar to market? Find past employees. Find ex-founders. Talk to them. Do not be blinded by the perception bias of only talking to founders who succeeded. Who tried and failed?

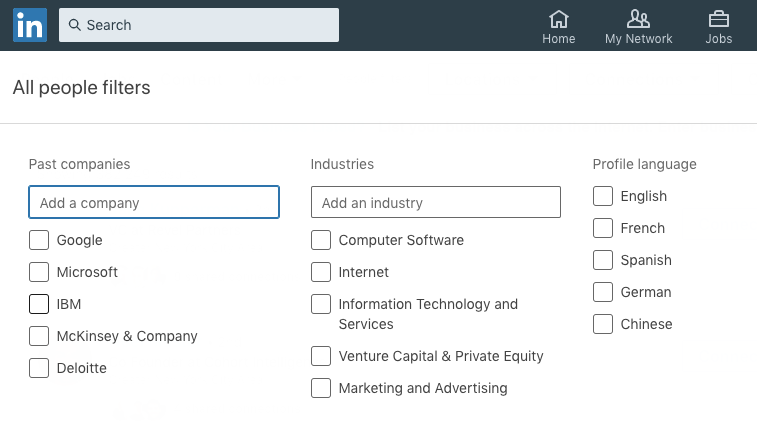

Finding these people isn’t as hard as you think. We do it all the time when diligencing potential investments. LinkedIn’s Past companies search is your best friend. Sure, current founders may be reticent to share details. Past investors and employees? Much less so.

Interview them to understand what success and failure look like. Ask them questions like:

- What drove your business model? What were your margins?

- How did you acquire customers? How much did this cost? How did customer acquisition change over time?

- What kinds of people did you hire? What kinds of things did you outsource?

- What were the major inflection points of your business? How quickly did you grow?

- How much funding did you raise? When, why, and from whom?

- What was your competitive advantage? Could you sustain it?

- What were your biggest challenges? What do you wish you knew before you started?

Before embarking on an entrepreneurial journey, particularly one in a new product space, seek to understand the models that have worked before. Have intimate knowledge of previous attempts at your maze. In the same way that business plans don’t help you run a business, these won’t provide you with a complete map of the journey ahead, but they will increase your chances of avoiding common pitfalls, finding your cheese, and navigating out the other side.

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.