Kickstarter, Indiegogo and other crowdfunding platforms are often misunderstood. It definitely isn’t investment: It’s debt.

Hardware startups struggle to manage their cash. It’s common to pay for large expenses (like tooling and inventory) 9–12 months prior to selling your product. This is why pre-order campaigns have been transformational to the hardware ecosystem: they can solve the cash flow crunch of the first production run.

But while crowdfunding is a powerful tool, it’s also one of the most misunderstood. There are a host of lesser-known financing options available to help with cash flow. This post aims to expose these options and help young hardware startups navigate the world of debt financing.

Debt is a Powerful Tool for Hardware

Aside from raising money from equity (and convertible debt), there are four common types of debt that hardware companies lean on: crowdfunding/pre-sales, factory financing, PO financing, and venture debt.

#1 Pre-sales

Because pre-sales are often the first money a young company brings in, it often gets confused with equity financing. You even hear it in the way people talk “we raised $1M on Kickstarter.” In reality you haven’t raised any money at all, you’ve pre-sold product. Kickstarter and Indiegogo serve a valuable place in the hardware funding ecosystem but do not be mistaken: pre-sales are debt not equity. Every dollar you “raise” must be repaid with a product.

Crowdfunding dollars should be focused on production costs (tooling, inventory, packaging, logistics) rather than development costs (customer development, prototyping, salaries).

Like other kinds of debt, there are harsh penalties if not repaid on time (delivering late can destroy your reputation). My standard advice to consumer product founders looking to fund their companies with crowdfunding debt: use it only if you’ve completed product development (have an EP) and know your precise BOM, COGS, fixed costs and distribution margin.

#2 Factory Financing

Factory financing is the most powerful form of financing for hardware companies. It usually comes as a line of credit (sometimes known as payment terms) extended by your contract manufacturer (CM). Instead of the CM requiring you to pay for parts and labor upfront, a line of credit allows you to delay that payment by 30 days or more. Unfortunately, CMs rarely extend credit to small startups during their first production run.

If you’ve never worked with a CM before, 50% payment upfront and 50% FOB (freight on board, when your product is put into a truck) is standard. As you build up your credibility as a business, credit is first issued as Net 30 (30 days from FOB). Over time, CMs may extend credit to Net 90, Net 120 or longer.

There are some high-growth consumer hardware success stories that wouldn’t have scaled without exceptionally good terms from their CM. GoPro famously raised a skimpy $88M in total from venture capital firms before going public, despite having annual manufacturing costs of >$500M. This was enabled by a $100M line of credit (and $200M investment) from Foxconn, their CM.

Because manufacturing costs often run into the millions, CM financing can have an outsized impact on cash flow and will prevent you from using your limited equity pool for production runs.

- Key Terms: Net 30/90/120/etc, draw requirements, provisions of default, monthly forecasts for unit volume

- Providers: the CM you use for final assembly (the larger the CM, the more likely it is to get better payment terms), occasionally banks and other financials institutions but only if you have A-1 credit and excellent relationships

#3 Purchase Order Financing

If you’re lucky enough to get a significant purchase order from a brand-name retailer (or well-known B2B customer) it’s often possible to convince startup-friendly banks to provide debt financing based on pending sales. There are also financial institutions that specialize in PO financing that can be more lenient than banks. If you’re selling $2M worth of product, the lender may advance your CM $1M to manufacture the product and then collect the payment directly from the retailer. You pay for this with fees based on the amount of time between when the cash must be provided to the supplier and then the customer/retailer pays.

- Key Terms: 2–4% per 30 days of utilization of the supplier-side capital, may be minimum capital requirement, may cost more if guaranteed payment clause from retailers

- Providers: Silicon Valley Bank, Square 1, Comerica, Bank of America, Paragon, Commercial Capital

#4 Venture Debt

Rather than betting on the potential of the business (like equity investors do) venture debt is mainly betting that your existing investors will keep financing the company. Having access to venture debt often requires investment from brand-name VCs. Often these investors will have to communicate to the venture debt firm that they have significant capital in reserve to fund the company going forward. The amount you can raise will depend on how much venture capital you’ve taken in and you’ll usually issue warrants as downside protection. Defaulting can yield major challenges to your cap table and even the need to file for bankruptcy. Venture debt sits above all equity on the preferences stack so many founders and investors do not like venture debt.

- Key Terms: 5–15% interest, 6–12 months of draw, 2–4 years until maturity, 1–5% warrant coverage, right to invest in future equity rounds, early-payment penalties, etc

- Providers: WTI, Comerica, Lighthouse, Hercules, Pinnacle, Horizon, SVB, Square One, some venture capital/debt firms during equity financings

The Big Picture

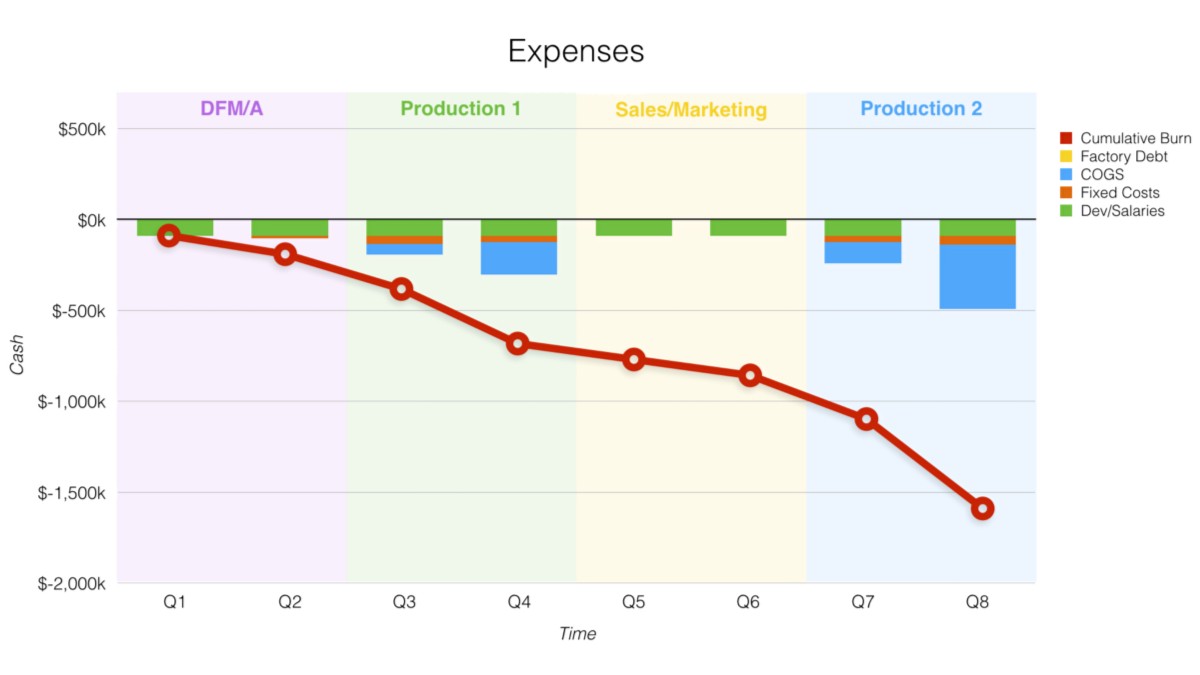

To illustrate how debt can improve the bottom line, let’s compare two different scenarios. We’ll use the data outlined from the fictional Bolt-o-Phones product we built in the previous post: Will Your Hardware Startup Make Money? As a reminder, we hired a team to develop the product, built 5,000 units in China, sold them, and then did a second production run 10,000 more units, all over the course of two years. Here’s what that financial picture looks like (note that all revenue and equity has been left out for simplicity):

Without looking at revenue or equity of any kind, we can see how much capital it takes to scale a hardware business. By the time we’ve made 5,000 Bolt-o-Phones, we’ve spent $690k. By the time we’ve made 15,000 Bolt-o-Phones, we’ve spent $1.6M. And, if this is financed by private investors, the company will have given away ~15–20% equity for $1M of production costs. While this is sometimes unavoidable, here’s what the same story looks like leveraging a line of credit from our contract manufacturer:

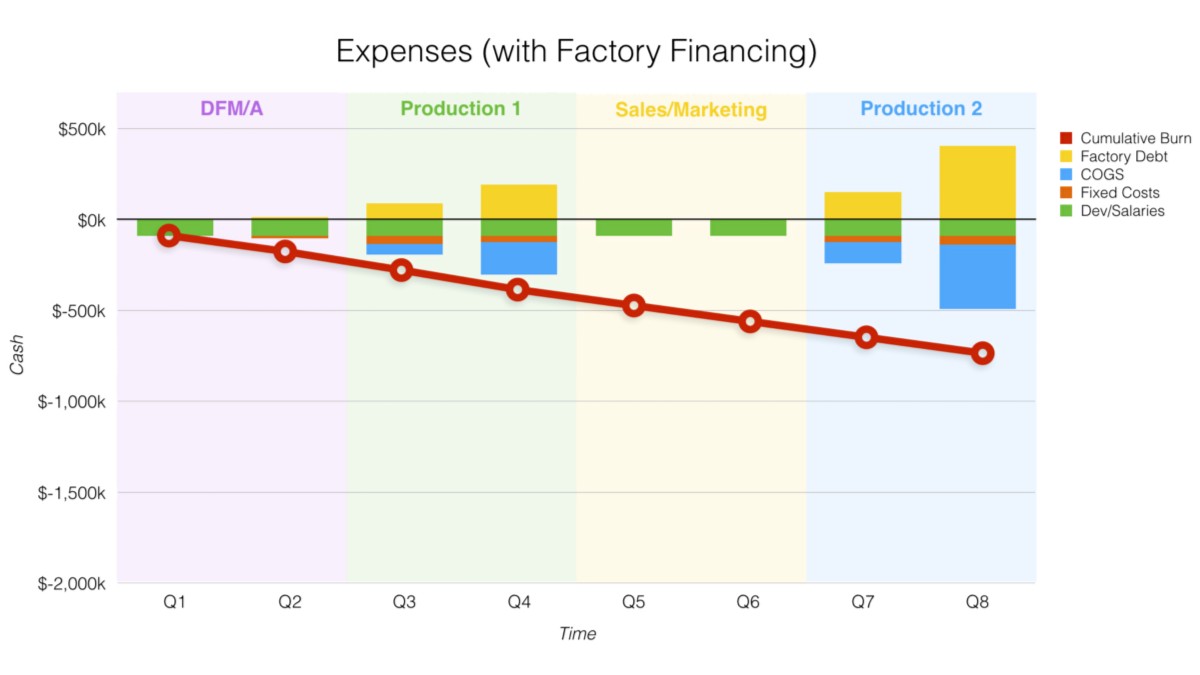

This financial picture is very different. The company has a predictable burn rate and uses the line of credit provided by the factory to offset the timing of production expenses. This allows founders to keep the ~15–20% of equity they would have otherwise had to sell to finance production. While debt from the factory still needs to be repaid, net 60 or net 90 terms allow the payments to be made after the retailer/customers have paid for their Bolt-o-Phones. When hardware startups realize how powerful this is, it’s a watershed moment.

Financing manufacturing with equity should be avoided as much as possible; instead consider factory financing to offset expenses to align with revenue, preserving precious equity for the team.

Every financing option has its place in the timeline of a company. Using crowdfunding as a replacement for equity financing is just as dangerous as raising a high-interest round of venture debt too early in the company’s life. Debt can be especially dangerous if not used carefully: unlike equity it’s very hard to develop a plan B if things go wrong. When in doubt, ask an experienced investor that has dealt with all of these options, ideally someone who knows hardware financials.

Ben Einstein was one of the founders of Bolt. You can find him on LinkedIn.

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.