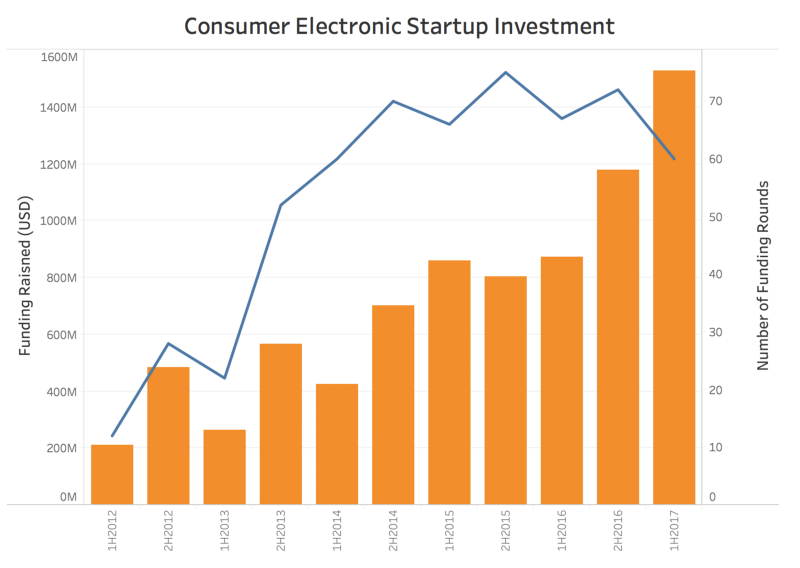

This is the third year I’ve published an overview of hardware startup investment trends (read last year’s here). In the first half of 2017, funding was up. We saw strong growth in both total dollars raised and number of funding rounds.

As in previous years, the San Francisco Bay Area continues to dominate the investment landscape. NYC’s numbers will look a bit better for 2017 (Peloton raised $325M in May), as will Boston’s numbers (Desktop Metal raised $160M this year), but they are still a drop in the bucket.

The funding gap between the Bay Area and other hardware hubs actually got wider in 2016. Among the ecosystems compared here, the Bay Area took 65% of total funding in 2015 but 75% of total funding in 2016. Network effects and economies of scale tend to make many technology markets winner-take-most. The power law phenomenon that drives city population and venture capital returns likely drives hardware community success, as well. While there has been some talk about the decline of San Francisco, the data does not yet support that narrative.

Hardware Malaise

Despite this increase in funding, there’s a feeling of malaise among many of the founders I speak with. They talk as if 2015 was the peak of the hardware hype cycle and assert that investor dollars have since dried up. It’s definitely true that the novelty of consumer 3D printing, wearables, and crowdfunding has worn off, but it’s not true that investor dollars have disappeared. In fact, consumer electronics funding is at an all-time high.

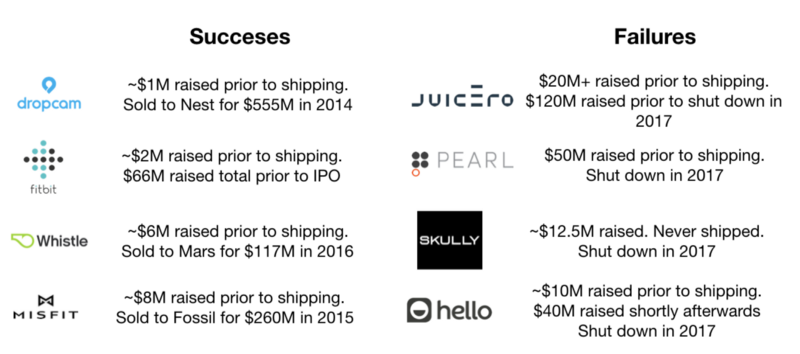

To be clear, venture capital dollars raised is often a poor proxy of success. Much of the malaise felt by founders this year is warranted, with the high-profile collapses of Juicero, Lily, Hello, Pebble, Jawbone, and Pearl. These are cautionary tales for founders and investors alike. While it’s hard to know exactly why these companies failed, from an outsider’s perspective, each has a lesson to teach us:

- Jawbone brought to market category defining products but ultimately struggled with the challenges of commoditization with a one-off sale, hardware business model. Competitive markets exert tremendous pressure, dragging companies towards lower margins and higher customer acquisition costs over time.

- Lily’s failure to ship highlights the difficulty of new product development and of managing risk. There are very few successful hardware startups whose first product is both high technical risk and high product risk.

- Juicero and Pearl illustrate the perils of raising piles of cash prior to product/market fit. While startups with high technical risk might need millions of dollars to complete product development, for most hardware companies, this is no longer the case.

The way in which you run a business is more important than the amount of money you raise. Large rounds of funding prior to product/market fit often lead companies to overspend in many tiny ways. Capital efficiency matters. As the outcomes above show, an early feedback loop with customers usually yields better outcomes.

Why Invest in Hardware ?

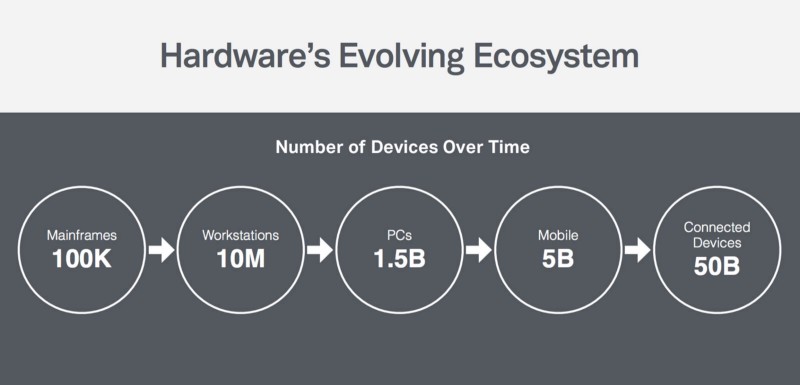

Despite these failures, institutional investment in hardware remains strong because a decade after the iPhone, we are again at a crossroads. While the shift to smartphones destroyed entire product categories like PCs, GPS, and digital cameras, it has also enabled countless new ones. The rise of the IoT, smart home, digital health, robotics, and now VR/AR are in large part due the connectivity and component supply chains created in service of the mobile industry.

While we’re a long way from leaving the mobile trend behind, we are at the beginning of the next computing platform shift because increasingly, interacting with a digital service doesn’t always require a PC or a smartphone. From smartwatches and connected speakers to intelligent ovens and digital art frames, smartphone supply chains have lowered the cost of product development and spurred an explosion of new hardware. To some, it’s an internet of shit. To me, it’s democratized creation, where more products get to market and consumers, not VCs, decide which products succeed.

It’s inevitable that many of these companies won’t succeed. Some products won’t find enough demand and never grow large enough to be a sustainable business. Others will be successful but commoditized by competitors. However, just as cheap cloud computing and better developer tools created a horde of successful SaaS companies, reduced costs of development are enabling a generation of hardware startups. Lower barriers to entry allow for more market participants.

By our count, we’re still in the early innings of this macro-trend. As we move through this trough of disillusionment, remember that in every hype cycle, there’s a kernel of truth. A few examples:

- Most consumer 3DP companies have gone bust, but Formlabs, focused slightly up-market at prosumers, is thriving.

- Pebble failed, and smartwatches were lampooned, but Apple sold more watches last quarter than ever before.

- An internet-connected exercise bike sounds, at first, like a bizarre IoT product, but Peloton did $170M of revenue last year and has a fanatically happy customer base.

While I’m sure we’ll see more failures in the coming years, the future for hardware is bright. Solve real problems, delight your customers, and remember that capital efficiency matters. We are living in a golden age of product development.

Notes:

- In past editions of this post, we had also published a graphic of the most active investors in hardware. We’re trying something new and publishing the list of investors behind that dataset. Find it, along with a primer on raising funding here.

- Everyone’s definition of hardware is a bit different. By “hardware”, we’re generally referring to startups focused on both hardware/software and made possible by the dropping costs of connectivity/components enabled by smartphone supply chains. Robotics, wearables, and IoT companies fit this definition. Most consumer goods companies do not. We think of consumer goods companies like Casper, Warby Parker, or Bonobos less as hardware companies and more as digital commerce brands innovating around distribution.

- Here’s the list of companies I included in the sample. The threshold for inclusion was $1M+ raised publicly as of the first half of 2017. I don’t include China in the analysis because I miss a ton of funding rounds there. The funding trends data also excludes rounds above $500M from super outliers like Magic Leap, Xiaomi, and Jawbone.

- Thanks to Crunchbase for help with the data set. Note that actual dollars invested are higher, as Crunchbase and public data tend to not capture all funding, especially early stage one funding.

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.