This is a 4-part series on what building a scalable hardware business looks like:

Part 2: Financing + Manufacturing

So you’ve built a small team and have a prototype that early adopters love, congrats! What’s next? Typically two things: raising money and building more product. Both of which can be exceptionally difficult if you haven’t done them before.

Before you can do much of anything in hardware, you’ll need cash.

One of the main differences between SaaS startups and hardware startups is capital. A big reason for this is manufacturing. Getting both financing and manufacturing right is critical to solving the single biggest problem of hardware: distribution. But we’ll cover that later.

Disclaimer

Please do NOT hold me accountable for the specific numbers here. These are averages, extrapolations, and circumspect data from my experience of designing, financing, manufacturing, and selling hardware products over the past several years. These numbers are highly variable and depend hugely on a large array of parameters; think of this as more order-of-magnitude approximations rather than hard rules. That said, feel free to comment where you can and help bring some objective transparency to the process of building a hardware startup.

Alright, part 2:

We get lots of questions from founders about raising money. Many assume they need to raise venture funding even though it’s often a poor fit with their business. The traditional consumer electronics model (selling physical products for money) is tough to profit from unless you achieve extremely large scale. Most crowdfunded hardware projects are a very poor fit for VC (e.g. coolest cooler). Still, for some companies that are working in very large, competitive markets, VC is one of the only ways to go. Here are some things to keep in mind:

A quick note: I’m explicitly not covering working or growth capital for hardware businesses even though this is an exceptionally important of any hardware startup. This is targeted at seed financing.

Venture capital is a game of outliers, not averages. The top 1 or 2 companies in a VC’s portfolio usually account for the vast majority of their returns. This is one of the fundamental mistakes many people make when looking to raise capital from professional investors. There are two main types of private investors for startups: individuals (angel investors) and funds (venture capitalists). While the dynamics of these investors are similar, VCs typically have a higher bar for investing due to their accountability to THEIR investors (limited partners). Due to the outlier nature of VC, nearly every investor is looking for an unlikely large success rather than a likely medicore success. Typically, ‘large’ means a company that can get to $100M of revenue (bookings) within 5 years or so. It’s extra challenging to raise capital if you don’t believe your business fits into this category. Before pursuing investors, make sure your business makes sense to finance this way.

Most VCs are ‘ownership driven’. This means they want to own a significant portion of companies they believe strongly in. A typical VC has a target ownership of 20% when leading a financing round. VCs that wind up with less than their target are typically less helpful than ones that do. VCs that ask for far more are suspect.

These numbers vary A LOT but the mean valuation for priced seed rounds that we’ve been involved with is $4.5M pre-money (meaning the price of your company prior to the infusion of cash). This is focused around east coast investors who tend to value companies lower than Silicon Valley investors, especially in the earliest stages of a company. Valuations at this stage matter less than most founders purport. The quality of the investor and their interest/motivation are far more important.

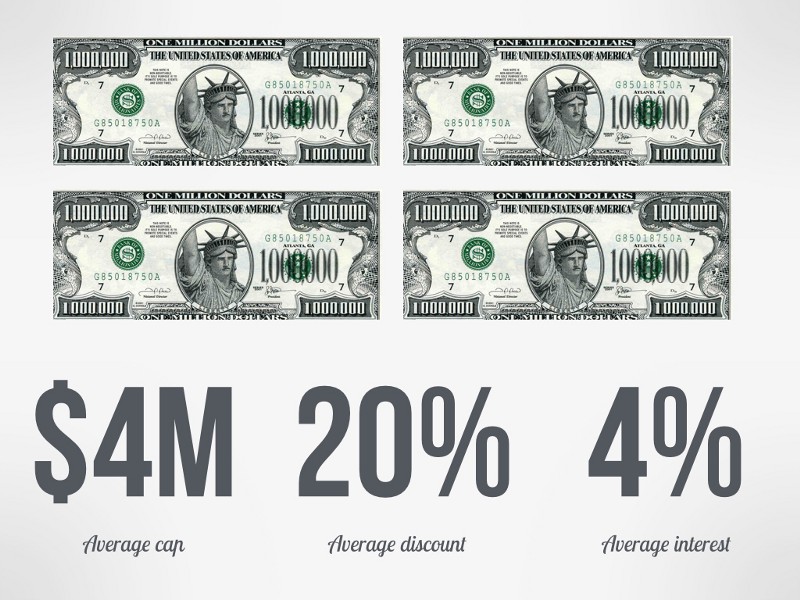

Again, hugely variable, but for founders who choose to raise their first financing on a convertible note (rather than a priced equity financing) we typically see a $4M cap with a 20% discount (10–15% is also quite common). Many inexperienced founders get too caught up in the “machinery” of financing (knowing how to raise a seed round) and get distracted from building an exceptional team, product, and company.

One other note about raising capital: this is usually the single easiest milestone you hit along the trajectory of a startup. Do not fall into the trap of emphasizing the ‘accomplishment’ of raising funding. When you take someone else’s money, you owe it back to them. It’s your job to return that capital with a nice multiple. Congratulations, you just inherited a new responsibility.

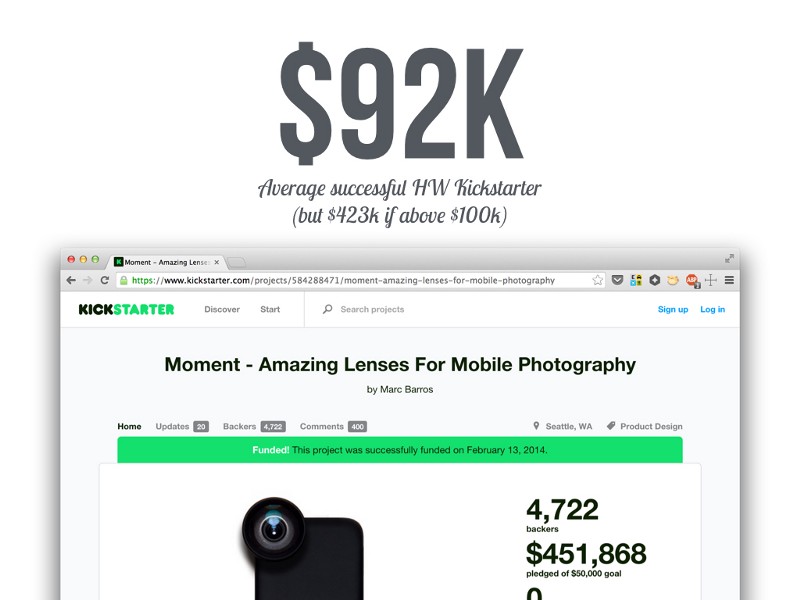

Many inexperienced founders believe that crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo are the modern day equivalent of raising capital from private investors. This couldn’t be more wrong. Crowdfunding can be a great product launch tool. It can also be a great way to be forced into a corner: building the wrong product in a small/niche market and running out of capital halfway into manufacturing. It happens to a huge number of successfully backed projects. Worse, the average hardware campaign raises only $92K (which is the equivalent of two or three small angel investors). It’s a lot of work for a small check. Don’t forget that after you deliver your product to backers you still need to go build sustainable distribution channels.

In my opinion, if you want to build a company (not just a product) the best way to use crowdfunding is AFTER you raise financing from private investors, once you’ve built a team and fully designed your product.

AngelList (www.angel.co) can be a fantastic tool for helping you raise capital from a broad set of private individual investors. It is not a place to post a deck for your company and ‘see what happens’. Just like crowdfunding, using AngelList successfully requires hard work, planning, and luck. The most successful companies on AngelList have a good portion of their round committed ‘offline’ before posting it publicly. This signals to investors and syndicates that you already have momentum.

So how much capital should you raise? This usually involves some combination of math and investor appetite. Some investors believe you should only raise enough capital for your next milestone. In hardware, these milestones are few and far between. More than any other metric, hardware startups should target the amount of time your company can stay alive, commonly referred to as ‘runway’. Hardware startups should shoot for 18 months of runway. This should include headcount, product development NRE, cost for first production run and a healthy margin for the inevitable oversights that come from first-time manufacturing nearly anything.

Part of the reason 18 months makes sense is it’ll take 3–6 months just to raise the capital. Companies should either be in ‘product mode’ or in ‘fundraising mode’. Don’t try to do both at the same time as both will suffer. Fundraising is more than a fulltime job.

If you’re like the average company, you’ll raise around 4 rounds of financing. If you sell too much of your company in each of these financings, you and your team will quickly be demotivated from lack of ownership. A good lead investor will understand this, but sometimes people get greedy. As a rough rule, don’t sell more than 25% of your company at any given time.

Just like customers, the conversion rate of potential investors is very low. On average, our companies see about one committed investor for every 10 they ask. The best way to ensure you’ll raise capital successfully is to make sure you’re talking to the right people. But if you’re raising from VCs, be careful of talking to too many investors before you get commitments. Everybody talks to everyone else and if investors keep hearing that others passed on your company, they will often be swayed to pass as well. We usually recommend pitching in tranches of ~5.

Your pitch deck is not designed to get a commitment from an investor; it’s designed to get a meeting or to pique their curiosity and get them to ask good questions. Keep it short, exciting, and vibrant. You’re making an emotional appeal to get excited about your future. Garr’s book Presentation Zen is a good place to start. Don’t tell people how much you’re raising in a deck.

Contrary to popular belief, manufacturing is not that hard if you know what you’re doing. However, If you’ve never done it before, it’s pretty much impossible. The single best thing you can do to ensure success in manufacturing is to work with someone that knows what they’re doing. Either hire someone with experience scaling production or contract a service company like our friends at Dragon Innovation.

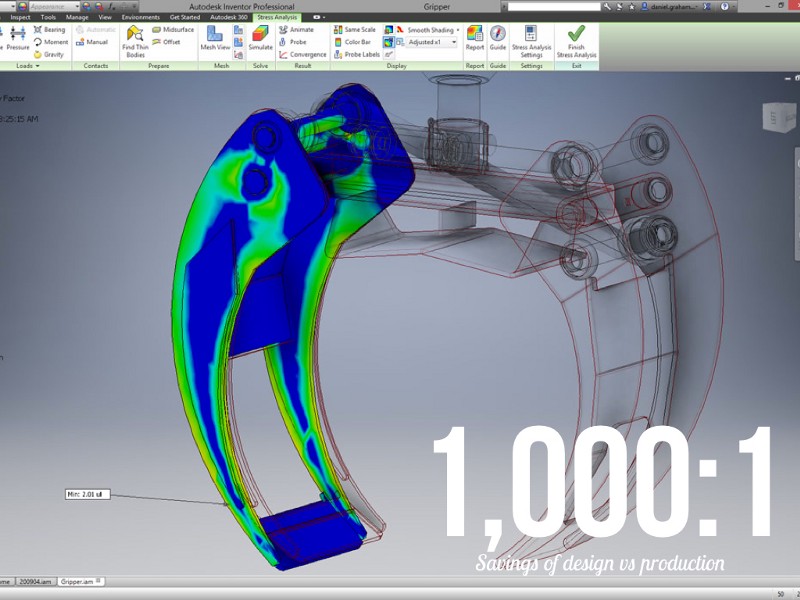

One of the largest mistakes first-time engineers make when it comes to manufacturing is thinking that the process is serial: product development ‘finishes’ and manufacturing ‘starts’. In reality, the two are viciously iterative. Very small details of how parts are designed can drastically change the manufacturing process. Time spent in design/engineering is far more efficient than time spent in manufacturing. A design that is ‘print ready’ (meaning it can be molded without changing geometry) can save hundreds or even thousands of person-hours in manufacturing.

Many products make sense to manufacture in south eastern China, especially when cost/margin matters and scale is expected to be large (like consumer electronics). The reasons for this are numerous. Manufacturing in China can be both astoundingly powerful and immensely frustrating. The next few points help chart a course for China.

Most Chinese contract manufactures (CMs) have a minimum order quantity (MOQ) of 5k units. More importantly, these CMs want to see a lot of growth (ie: your second production run is 10k units, your third is 20k, and so on). What really drives this is the total pass-through cost of product rolling through their facility. In the first year of production, a typical CM would like to see $1M worth of BOM leaving their factory for each customer. So if you’re building a really expensive product (like a 3D printer) a smaller MOQ is often okay.

If you don’t plan on making $1M worth of product in the first year, you typically have to get a bit more creative about how to make those first units. More on that in a separate post.

Once you decide to make your product in China (congrats!) you should go there and look around. Contrary to popular belief, it’s next to impossible to build a product using Alibaba or MFG.com. CMs are investing in your company just like a VC; would you ever agree to have a VC join your board without meeting them in person? Hopefully not. For a one week trip to China budget ~$3.5k per person for travel and expenses

Finding the right CM is like finding the right spouse or co-founder. In order to pick the right one, you have to start with a large number. We usually suggest 10–12. These should be selected from a list of CMs that have built similar products (i.e. if you have a product with a lens in it, you should talk to CMs that make cameras). Look for other products they’ve built and talk to the COOs or CEOs of those companies. How were the companies treated? What was the cost/quality/schedule of their CM versus the others they looked at? What happened when there was a problem?

Next, you’ll want to narrow it down to ~5 CMs that you’d like to engage with. This requires an in-person visit and hopefully a dinner with the factory boss or project manager. If you can’t have dinner with the owner of the factory, you’re probably too small of a client for them.

Now you’re ready to send an Request for Quote (RFQ) package to the CM to begin understanding the price they’ll charge you for the first production run and how long it will take to deliver. This is one part art and one part science; if you’ve never done it before, I strongly suggest getting help. A disorganized RFQ process is the single biggest mistake I see first-time hardware founders make.

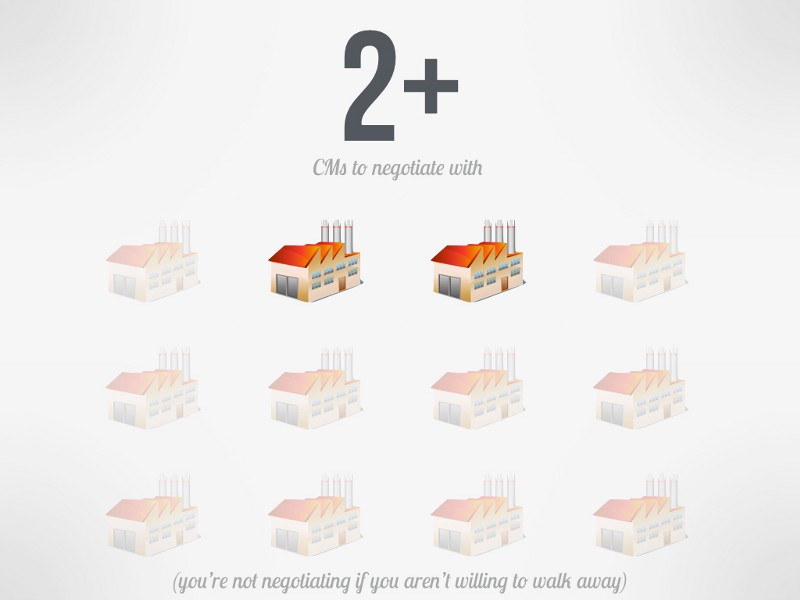

Another big mistake: picking the CM with the lowest price from the RFQ and running with them. Again, just like raising money from VCs, this is a business relationship and a negotiation is almost always involved. Select at least 2 CMs based on the RFQ and begin negotiating with the owner or project manager. You have three main dials to turn: cost/margin, timeline/schedule, and quality/care. Remember: you’re not negotiating if you’re not prepared to walk away from the table, which is why having 2+ CMs to negotiate with is so critical.

Once you decide on a CM, you have more finite details to negotiate (i.e. who pays for problems, how delays are handled, etc) as part of the Manufacturing Services Agreement (MSA). This process usually takes about 3 months but many CMs will actually start manufacturing your product before this is agreed to. This is usually okay, but tread very carefully.

Most CMs will quote around 180 days from database release (when you send the ‘final’ design to them) and when the product transfers ownership from the CM to you (typically called Freight On Board or FOB). Unless you’ve gone through the process before, it usually takes at least 50% longer than that and often stretches into 1 year territory. There are many ways to decrease this time, but most of them require capital, expertise, or huge focus from the founding team.

Most CMs require a large downpayment before any work is started and this is especially true for CMs working with small startups doing their first production run. It’s quite common to pay 50% of the total cost up front. This is so the CM can order components, cut tooling, and prepare for building the assembly line. It also separates the wheat from the chaff to signal to the CM that you’re serious.

As you make payments on time and begin to scale your product, CMs and suppliers will often extend large lines of credit to you. This makes it much easier to grow the manufacturing process but doesn’t help you much in the beginning (when you really need it).

Some startups spend huge amounts of time optimizing the cost of every single electronic component during the design phase. CMs have armies of people doing this and they’re much better at it than you are. Focus on the major parts that are difficult to change (typically the battery, microprocessor, and communications). There are often one or two other parts that are special for your product too. Don’t waste time finding the cheapest SMT resistors; your CM will do this better than you.

One of the largest fixed costs associated with manufacturing can be tooling. This unfortunately comes as a large upfront payment and represents one of the hardest/most expensive things to change once the design is released. This can vary by several orders of magnitude, but a simple injection mold tool (straight pull, single cavity, single shot, steel tool including texture/polish) averages around $6.5k in China. Keep in mind, most products that startups make can have between 5 and 50 different injection molded parts which can represent 1–50 tools.

In my experience, that exact same tool will cost a little more than twice as much in the US. It has also typically taken me longer in the US for the tools to be made (not entirely sure why that is though). Because the US and China use different mold base standards, it’s usually impossible to use tools in one country that were made in another, so don’t think you’ll just make product in the US first and then head to China when your volumes are higher.

A mistake I’ve seen over and over again is a product designed around the wrong microcontroller (MCU). A good friend of mine told me about the first version of their product (that eventually became extremely popular) but was originally designed around an obscure Motorola MCU that had a 26 week lead time and was $18/unit at scale. For a consumer product, this is a huge problem. Unfortunately, the MCU was doing a ton of complex math that had been painstakingly optimized to be power efficient. When the CM demanded that the MCU be swapped out to meet schedule/cost, the firmware took 6 months to rewrite for the new processor architecture. A 10 minute conversation with someone that had built high volume consumer electronic products could have saved this company 6 months of time. Do yourself a favor and pick the right MCU from the beginning.

No one is perfect. Manufacturing is complex so things inevitably go wrong. A small portion of complete products are usually thrown away during manufacturing, especially in the beginning of the production cycle. Startups often see around 5% of the products ordered scrapped. This often goes down to around 0.5% after a few production/design cycles.

Nearly all products need at least one product certification test (FCC, UL, CE, etc). These tests can be quite complex and expensive depending on the product but it’s tough to do this for less than $15k. Hiring an expert to help with this or reading great resources like Andy’s eBook can save you tons of time and effort. CMs can often handle this for you as well.

Each product comes in a cardboard box (often called a gift box). Basic single color boxes like the one pictured will usually cost $0.25 to $0.50 per box.

Unfortunately, companies like Apple have set exceptionally high consumer standards for packaging. I’ve seen startups spend more money on their packaging than any other single component. To me, this is a crime (but it won’t stop most people from doing it). High-end packaging with double side, two wall, 6 color printing, UV/foil, molded inserts, etc can cost up to $15 per unit.

All of these gift boxes are then usually put into another larger box called a master carton. These boxes are usually double-walled cardboard that typically costs $1 to $5. Many startups don’t think about packaging until the last minute. More than 75% of the BOMs I’ve seen don’t have line items for gift boxes or master cartons.

For part 3 on Logistics and Marketing click here.

If you missed part 1 on Team and Prototyping check it out here

Ben Einstein was one of the founders of Bolt. You can find him on LinkedIn.

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.