Last week, news broke that Pebble, one of the most beloved hardware companies of the modern crowdfunding age, is being “acquired” by wearable rival Fitbit. Press initially speculated it was a good acquisition, citing the 2M+ watches sold and two record-breaking Kickstarter campaigns. We now know this is not the case. Pebble is ceasing operations, shuttering hardware production, returning Kickstarter pledges, and filing for bankruptcy. How can a company that pioneered a new category with products people love go out of business?

I have immense respect for the path Pebble forged; selling and delivering 2M units of any product is an incredible feat. It’s hard to know exactly why they failed, but I’ve found learning from failure is one of the most powerful tools we have to help hardware companies prosper.

Crossing the Chasm

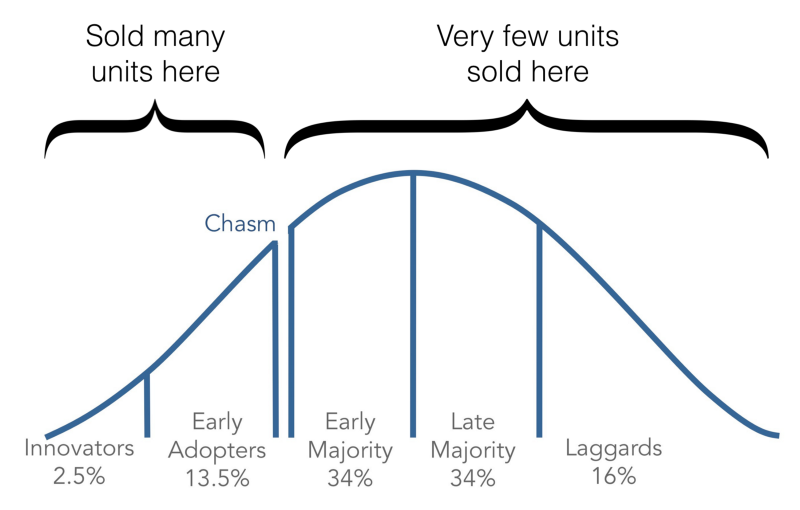

Many consumer hardware startups think being first to market with breakthrough technology will make them successful. While Pebble was a category-defining product, being first is not what ultimately drives long-term success. With low-cost (<$200 MSRP) consumer electronics, massive scale is fundamental to long-term survival. Pebble did an exceptional job selling product to innovators and early adopters, but struggled to sell to the critical early majority population:

Companies that sell low-cost consumer electronics must be solving a problem that early and late majority populations identify with. This is not to dismiss early adopters: they are an essential ingredient to get any startup to the next step. Both Fitbit and Pebble did an excellent job of building products that early adopters love, but after selling a few million units the primary question becomes, “how do you access the middle of the bell curve?” or “cross the chasm.”

As Apple is now learning it seems fitness, not productivity, drives most consumers’ desire to own a smartwatch. In the last year, Pebble refocused their product line and messaging around health but it was too little too late. For a low cost consumer electronic to cross the chasm between early adopters and the early majority, the product must address a problem that resonates with mainstream audiences. In the battle for real estate on middle America’s wrists, fitness has so far won over productivity and Pebble couldn’t pivot fast enough to respond to the market. Apple’s deep pockets gives them another shot.

The Margin vs Scale Dilemma

Pebble’s CEO, Eric Migicovsky, famously remarked Apple’s watch is the “Rolex” of smartwatches and Pebble is the “Swatch.” While it’s often far easier to sell lower-cost items to early/late majority populations, it’s a far more difficult path for hardware startups due to competition on margins. Pebble sold over 2M units over its 4 year production life; to many small hardware startups that’s impressively large scale. But in low-cost consumer hardware, even ~500K units per year isn’t enough to unlock the financial tools necessary for sustained growth.

Most companies have two options to get out of the margin vs scale dilemma:

- Increase the price or lower the cost such that it’s a high-margin product (which is usually over 50 points gross). This could also involve selling other high-margin services after the initial hardware sale. This often allows companies to find debt financing and/or self-financing inventory using revenue.

- Show large (>100%) annual growth rates enough to incentivize VCs or other private investors to finance the company with equity betting on large future revenues. This is the path most startups take. Unfortunately, the smartwatch market is actually shrinking (or so says IDC) which makes high growth rates difficult.

We can’t be sure of exactly what Pebble’s margins or unit volumes were, but last week’s news means it’s unlikely they were able to solve the margin vs scale dilemma.

Brand

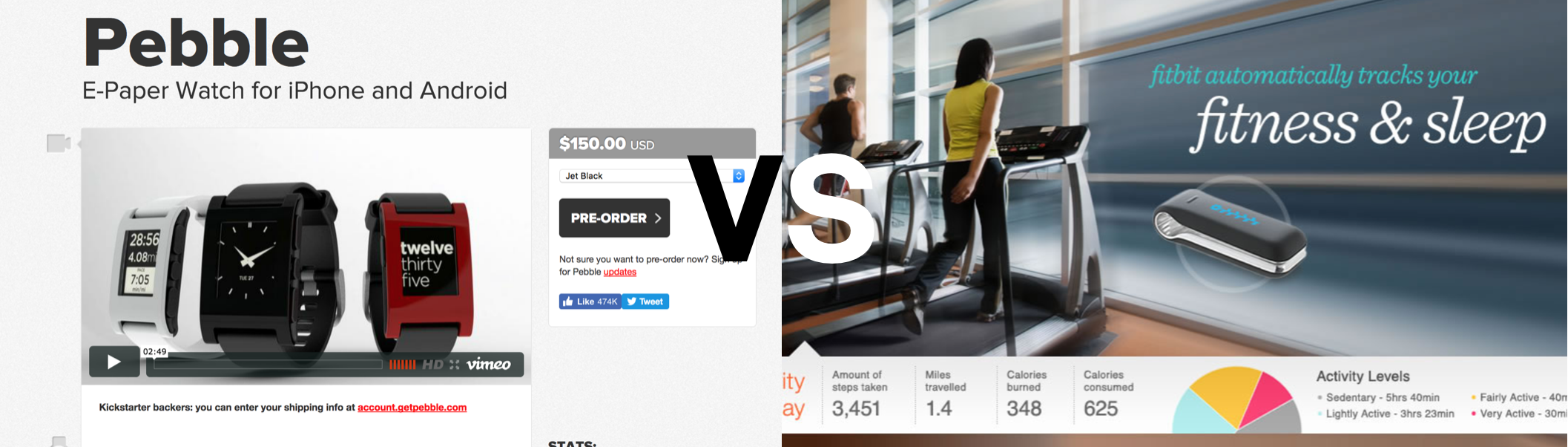

Ultimately, the most valuable thing consumer product companies have is brand. As the first smartwatch company, Pebble’s marketing engine was designed to build awareness and educate people on the novel benefits of having a screen on your wrist. This type of “feature marketing” is how nearly all tech products get started; Fitbit and Pebble looked similar one year into launch. But even then, you could see Pebble focusing on “what it is” rather than Fitbit’s “what it does”:

Over time, consumer electronics companies must transition out of feature marketing to “brand marketing”. Brand value is built by accessing emotions that consumers aspire to feel. This type of marketing is more akin to CPG companies like Nike or Coca Cola than tech hardware companies. Many hardware startups struggle to make this transition. Take a look at two screenshots from the homepages of Pebble and Fitbit today:

Two things are immediately clear to me with this example:

- Pebble has been steadily moving away from “e-paper watch” feature marketing to higher-level “value” marketing of what the product can do for you. But it’s still focusing on the product as the focal point of it’s marketing strategy.

- By always focusing on how consumers use Fitbit and why they care, the company has gotten incredibly good at accessing the emotions of fitness rather than depicting the products they sell.

Onward

The smartwatch story is far from over. Much of Pebble’s assets (and people) will forge on, using what they’ve learned to help Fitbit grow into the watch market. I hope Pebble’s arc can help consumer hardware startups learn how critically important scale and brand are to building long-term enterprise value: they above all else allow companies to prosper.

Ben Einstein was one of the founders of Bolt. You can find him on LinkedIn.

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.