This is Part 1 of a 4 part series on the hardware product development process. Head over to Part 2 (Design), Part 3 (Engineering) and Part 4 (Validation) if that’s more relevant for you.

Building a product that customers love is often the difference between a $1B company and bankruptcy. But with the cost and time requirements of the hardware world, startups really only get one chance to ship a product. Failure and iteration isn’t an option like it is for software startups.

If building a great product is so important, why do most hardware startups we talk to reject any sort of process for product development?

This series of posts is designed to shed light on what a good hardware startup development process looks like.

Yes, You Have a Process

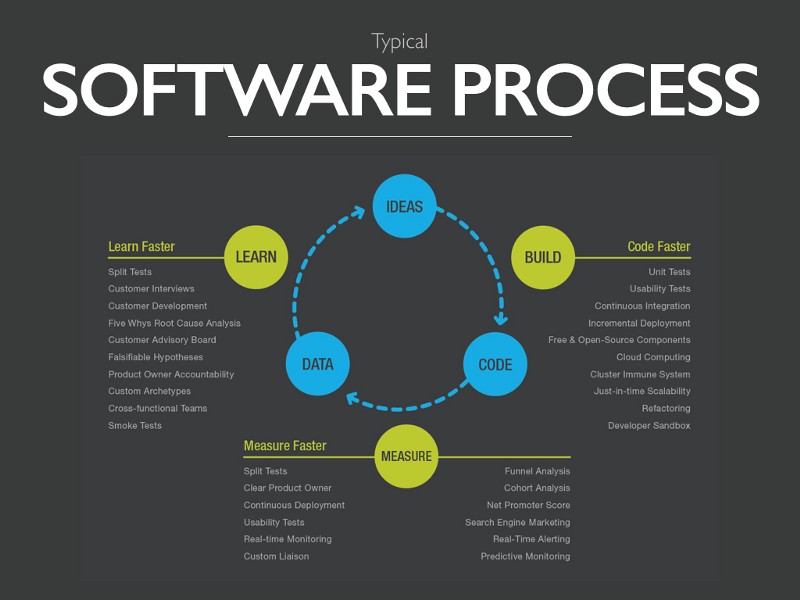

Startups seem to have an allergic reaction to anything that imposes order. Yet, most software startups have vocally supported adopting the Lean Startup process popularized by Eric Ries:

The build-measure-learn loop has become engrained in the software startup culture but is incomplete for hardware startups. Most hardware startups embrace a product development process that looks something like this:

Most startups think the hair-on-fire methodology is faster because it’s “less overhead” but in the long run this couldn’t be further from the truth.

Hardware product development requires more planning than software development. This is driven by the sheer number of things that must be done right before shipping a connected hardware product. Many of these things have long lead times and high costs if done improperly. A tiny mistake in design or a poorly QC’d part can bankrupt you.

The Process

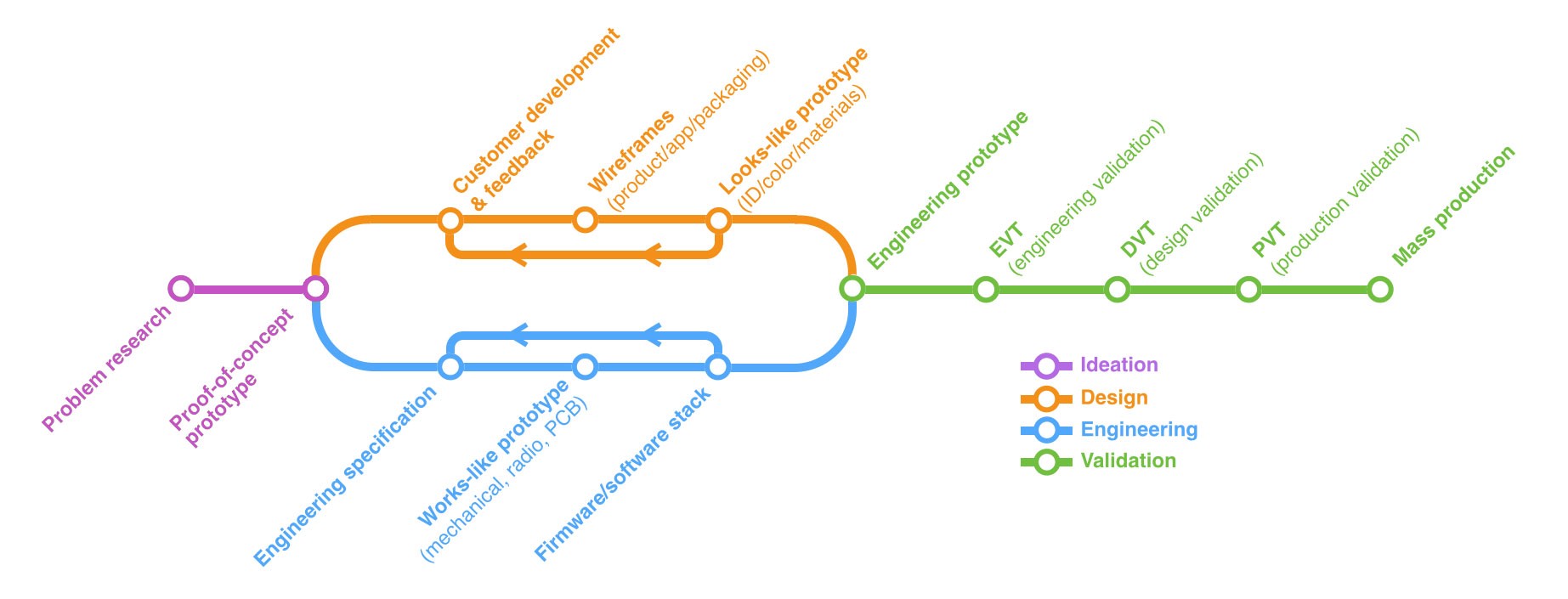

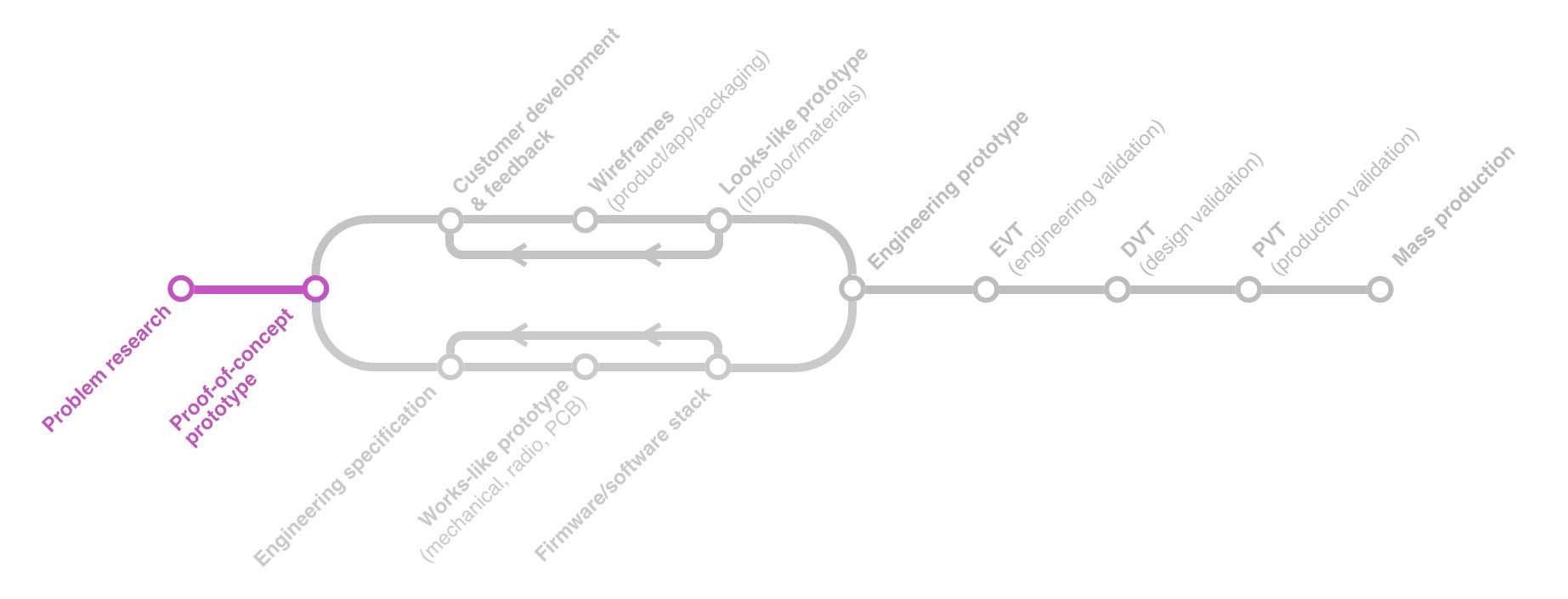

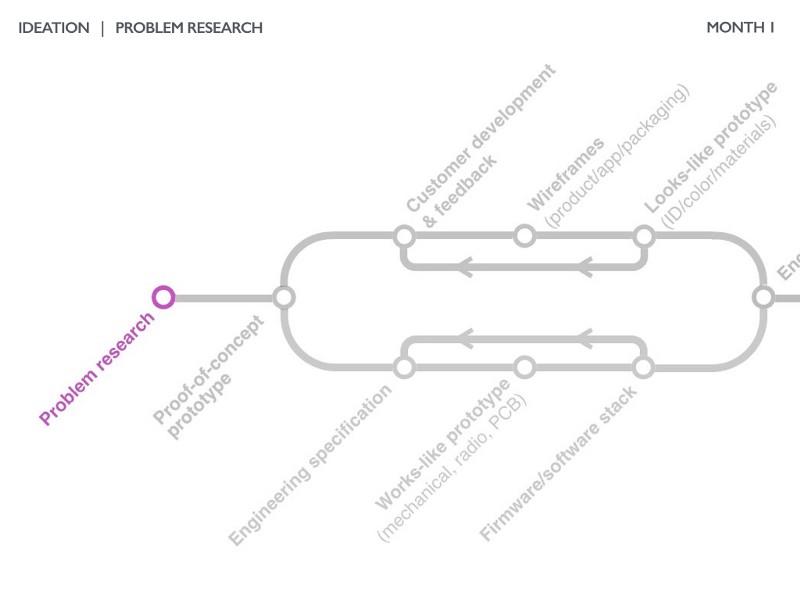

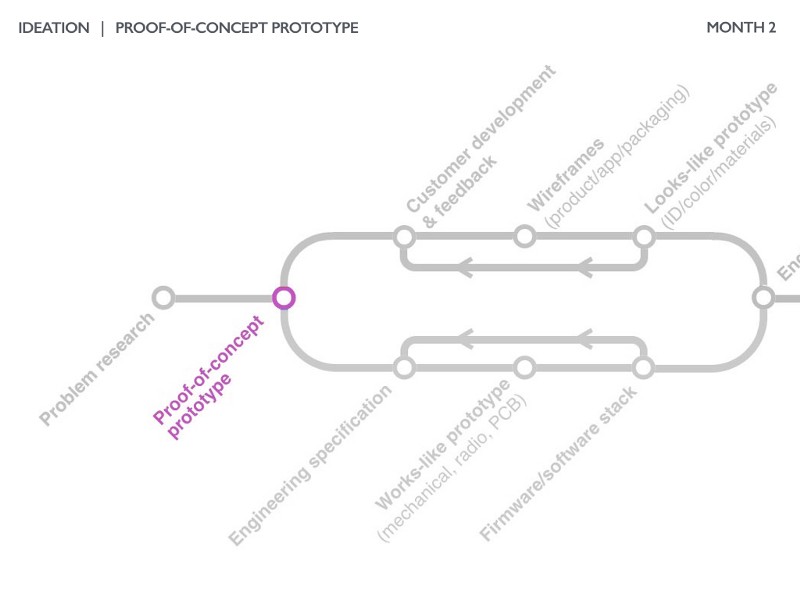

The process we use at Bolt is a hybridization of heavy-handed processes prescribed by the manufacturing/quality community and lightweight processes used by many design professionals. It is divided into four general phases: ideation, design, engineering, and validation.

To better illustrate this, we’ll follow a specific product that was designed using this methodology: DipJar (one of Bolt’s portfolio companies).

DipJar is a young startup building a simple product used to accept tips and donations from credit cards (rather than cash). DipJar doesn’t sell their product outright: each customer pays a fixed monthly fee per jar in addition to a small percentage of each transaction.

The company was founded by Ryder Kessler and Jordan Bar Am in New York City and has raised a relatively small amount of capital. Yet, they’ve successfully shipped many units to customers and demonstrated product/market fit. Much of this early success is directly related to the company’s focus on customer-centric development and iteration.

Part 1: Ideation

Ideation starts with clearly defining the scope of the problem and ends with a proof-of-concept prototype. Spending more time here will ensure founders lay a strong foundation for the rest of product development.

Problem Research

Too often engineering founders jump into building product without stepping back to concretely define the problem they’re working on. Understand your problem space first with customer development interviews.

When interviewing potential customers:

- Have fluid, unscripted conversations and be open-minded about where the conversation may lead you

- Don’t talk about your product or solution

- Take detailed notes or recordings to build a database

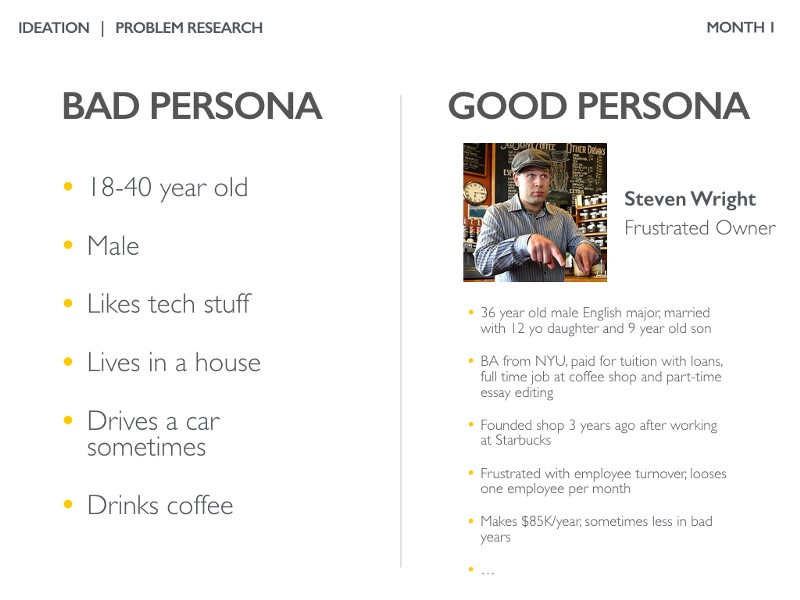

- Work towards building 3+ customer personas

- Don’t only focus on what people say, also pay attention to how they say it.

Nearly every company starts with an “ah ha” moment — an anecdote connecting the founder’s experience to the problem they’re solving. For DipJar, that moment was in a coffee shop. While a student, Ryder would frequent the local Starbucks a few times a day and became friendly with the barista staff. One afternoon it was exceptionally busy and the staff looked miserable. “At least you’re collecting a lot of tips,” Ryder remarked. “Actually, no one tips anymore due to credit cards. We’d rather the store be empty.”

As Ryder talked to more people, he realized it wasn’t just baristas that were affected by the decrease in cash transactions. Ryder also talked to musicians (especially those performing on the street), service providers (like barbers), and charities (including Salvation Army and The Children’s Miracle Network, both early customers of DipJar).

Conversations like these are the basis for building customer personas, which are fictional, generalized profiles of your ideal users. Having lots of these conversations will also equip you with a database of anecdotes to pull from to inform the rest of the product development process.

We love talking to companies that have built personas like those on the right. It shows depth of knowledge in a problem space.

Good problem research usually follows this checklist:

- If it’s a B2B customer: you know which stakeholder at the company makes the decision, how they purchase products like yours, and why this is a “top 3” problem for them

- If it’s a consumer customer: you know what brands they identify with, which designated marketing areas they live in, and their purchasing habits

- You have research to support how much they would pay for your product

- You have a beachhead customer base defined and a total customer base sized

- If you plan on raising venture capital, you can demonstrate how these numbers equate to $100M of revenue within 5 years

If you can check off each of these items, you’re ready to begin to think about how to solve this problem.

Proof-of-Concept Prototype

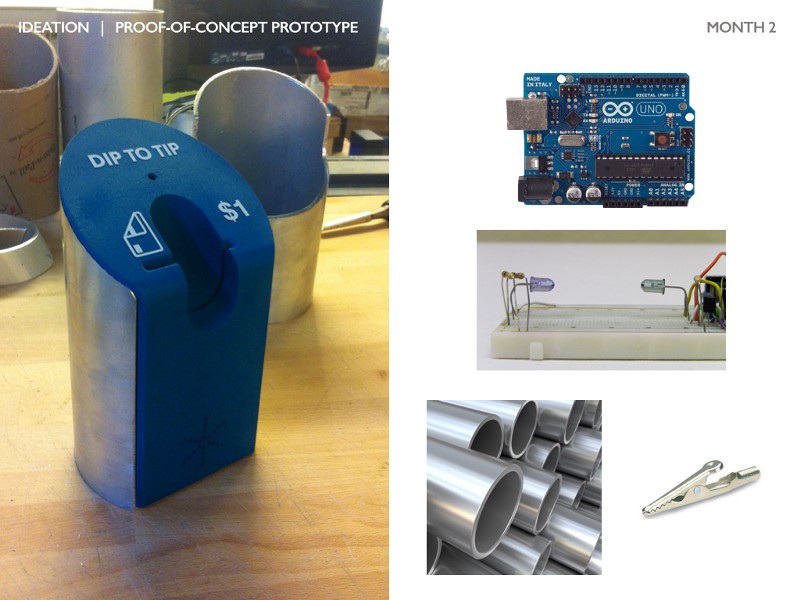

Proof-of-concept (often abbreviated “POC”) prototypes are all about validating the major assumptions your problem research uncovered. In DipJar’s case, the team had some major questions to answer:

- Can people figure out how to use a DipJar within 5 seconds at a counter during a transaction?

- Was collecting cash along with credit cards important?

- Are shop owners/employees supportive of having a DipJar on their counter?

These are fundamental questions to DipJar’s viability as a business. They quickly built prototypes to test these assumptions. The three prototypes above were built in a few days using off-the-shelf parts (an Arduino, a simple infrared detector/emitter pair, some aluminum tube, and a bit of spray painted plastic).

Even though DipJar’s primary purpose is to charge credit cards, they didn’t have time to implement that (nor was it critical for testing these assumptions). So these proof-of-concept prototypes don’t even have a card reader, just a way to detect and count how many times a credit card was inserted.

The team took jars to various target customers and left them there for a day. When the POC jars were collected, the team could tell which jars were more effective.

As it turned out:

- People easily figured out what a DipJar was and how to use it within 5 seconds of seeing one for the first time

- Most places preferred to collect cash in their own jars (and thus the cash “basket” in the DipJar never made it beyond this prototype)

- Owners and employees were okay with giving up a bit of counter space in exchange for more tips

Like any prototyping process, building a POC prototype is iterative. Some tips for this process:

- Come up with lots of ideas before building anything and evaluate the best one(s) to prototype. Some founders like using formal tools (mind mapping, superstorming, group ideation, brainstorming, etc). I’ve found that these techniques tend to be less effective than informal tools (conversations, mockups, and prior art searches).

- Focus on testing assumptions

- Prioritize speed over quality (this is very hard for engineers to do, but critical in this step)

- Use off-the-shelf parts vs building parts from scratch

Now that we have a good understanding of the problem and how we’re going to solve it, it’s time to optimize the solution so customers can use it. On to Part 2: Design.

Ben Einstein was one of the founders of Bolt. You can find him on LinkedIn.

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.