I have always avoided writing.

As a mechanical engineer, I would rather do just about anything else: sketch parts, build prototypes, or collaborate with manufacturers.

For over 15 years, I have designed and engineered products — mostly at IDEO, Apple, and Bolt. Contrary to my pre-disposition, I have found that writing is the most efficient way to build a better product. One document, in particular, has the highest impact on optimizing product quality, development speed, and production cost: the Product Requirements Document (PRD).

At Bolt, we help our portfolio companies quickly define their product requirements before we start designing. We use a simple, fill-in-the-blank PRD Template:

Why write a PRD?

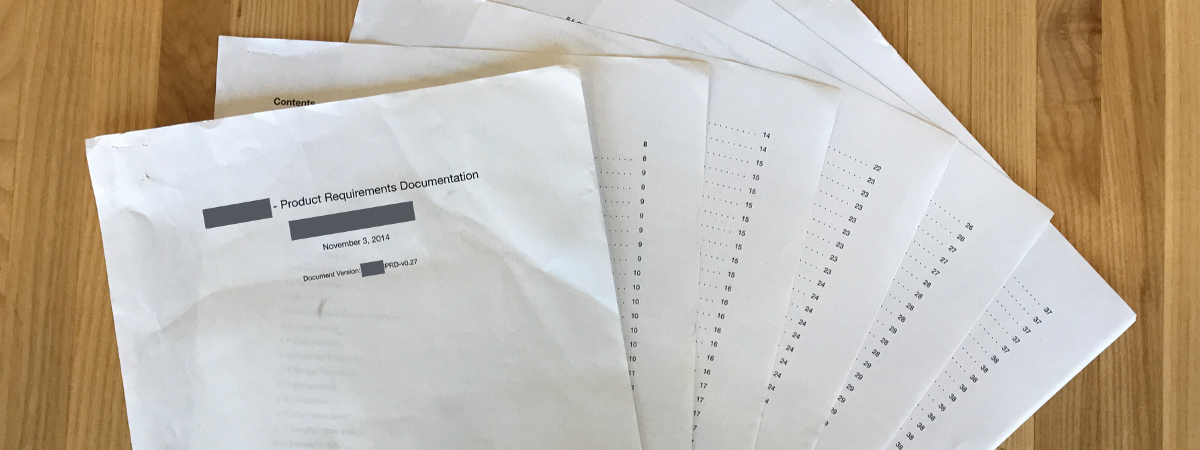

Like me, many designers and engineers are reluctant to create documentation — and for good reason. When I asked founders from our portfolio to share their experiences, I heard about 42-page PRDs that were essentially a full-time job to maintain.

We strongly suggest keeping your PRD lean and useful. It’s much better to have a simple PRD that you maintain and feel good about, rather than an exhaustive list of every detail that constantly has to be updated.

Even the very act of writing a PRD adds a ton of value in a few strategic areas:

1. Aligning Your Team

Even with teams of two people, there can be miscommunications about the product intent. Writing product requirements together is a great way to ensure your entire team is on the same page. It’s also great to revisit if disagreements arise and to share with new people when they join the team.

2. Seeing Around Corners

With nearly every product, teams run into a few unforeseen issues. For example:

- Will the electronics require FCC certification?

- Does each component need its own serial number?

- If a product breaks, will you offer to repair or replace it?

Uncovering these issues before you start the design process can save months of backpedaling and re-work.

3. Constraining the Design

It’s counterintuitive, but designers and engineers thrive on constraints. It’s easier to make decisions in a defined solution space.

For example, if someone asked you to build a doghouse, it would be hard to know where to start and even harder to know whether or not you did a good job. It would be faster (and more fun) to be asked to build an Eichler-style doghouse for a 10lb chihuahua that would protect it from 80 kilometer per hour winds, 40 centimeters of snow, and the neighbor’s eye-poking two-year-old. I’d bet you already have creative ideas for that one, and criteria for success.

How Writing a PRD Helped Dor

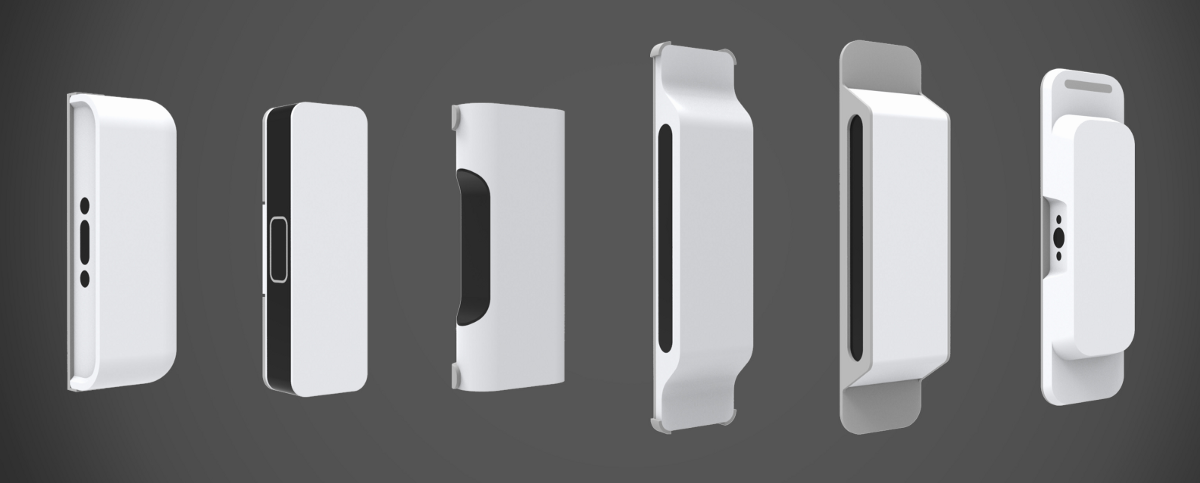

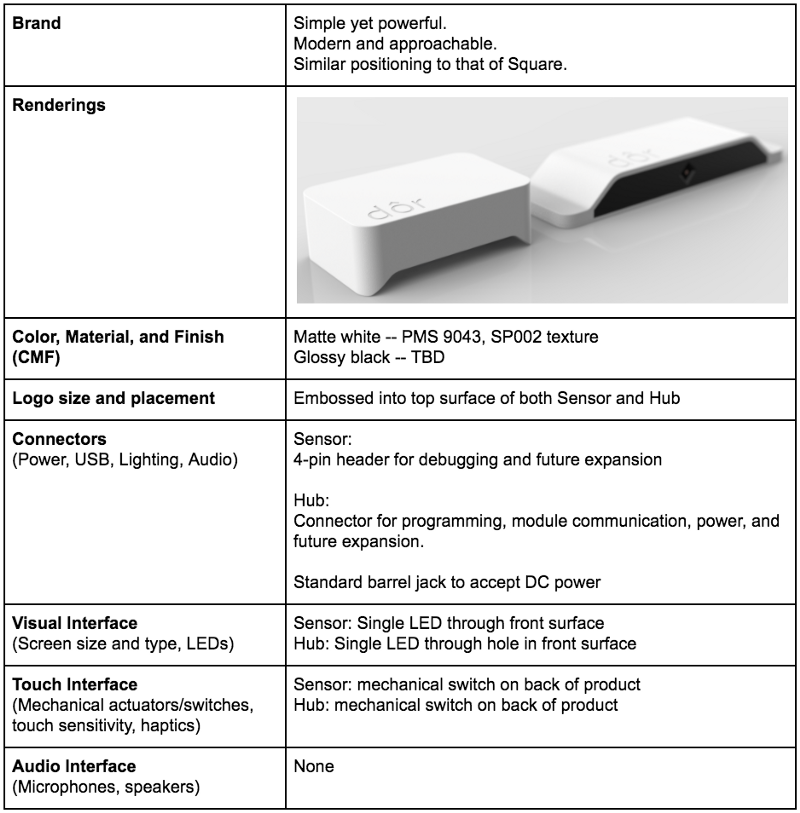

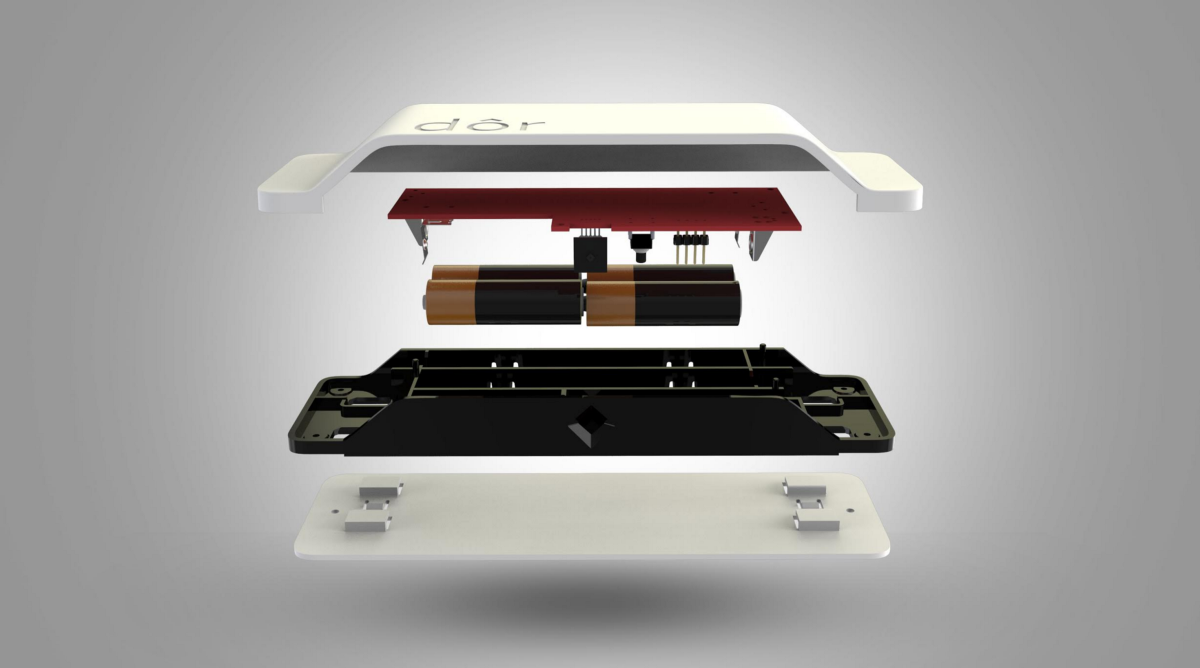

Dor, one of Bolt’s early portfolio companies, provides foot traffic analytics to retail-business owners. Their hardware includes a battery-powered wireless sensor that store owners install above the store’s entry way and a cell-connected hub that they plug into an outlet somewhere else in the store.

For reference, let’s walk through Dor’s PRD. We won’t cover the entire template, but I will highlight a few illustrative sections:

Product Description

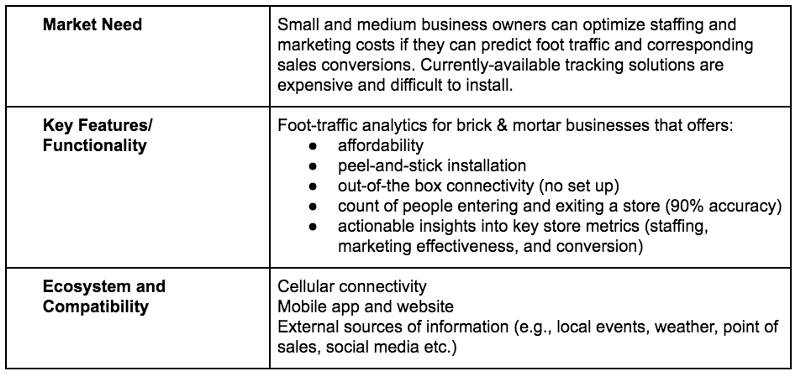

Why does the world need the product? What does it do? Are there other products or systems with which it needs to work? Dor saw an opportunity to help businesses optimize staffing and marketing efforts:

Notice that there are no technical specifications mentioned here. A PRD should focus on the attributes that will make the product successful and not the nuts and bolts of how those attributes are executed.

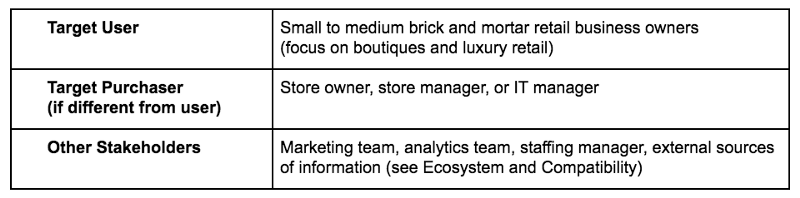

Stakeholders

Knowing who will use your product is just as important as defining its functionality. Is the person who uses the product the same as the person who buys it? Are there other stakeholders to be considered? What about those who ship it, sell it, install it, set it up, train others, repair it, or recycling it?

Be as specific as possible when defining your target market. You should never be designing for “everyone.”

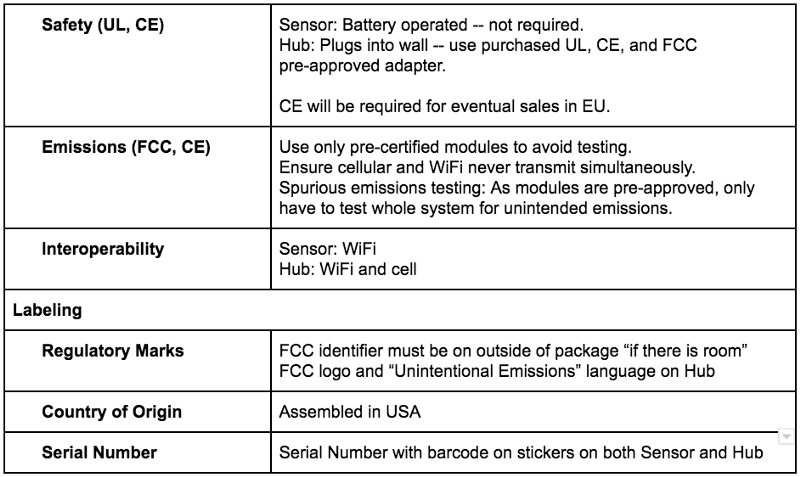

Regulatory

Next, focus on the markets you are pursuing and what is required to sell in those markets.

For example, any wireless product sold in the US must be approved by the FCC and labeled accordingly. Will you use a pre-approved radio module (less development but more expensive) or design your own (more development but less expensive)and have it approved?

Dor’s sensor required a serial number and an FCC ID, so the plastics were designed with space for labels. This was a fairly simple constraint, but still one worth thinking about from the beginning. For much more complicated products, like medical devices, you’ll need to organize your team around navigating FDA requirements; consider hiring a specialized consultant.

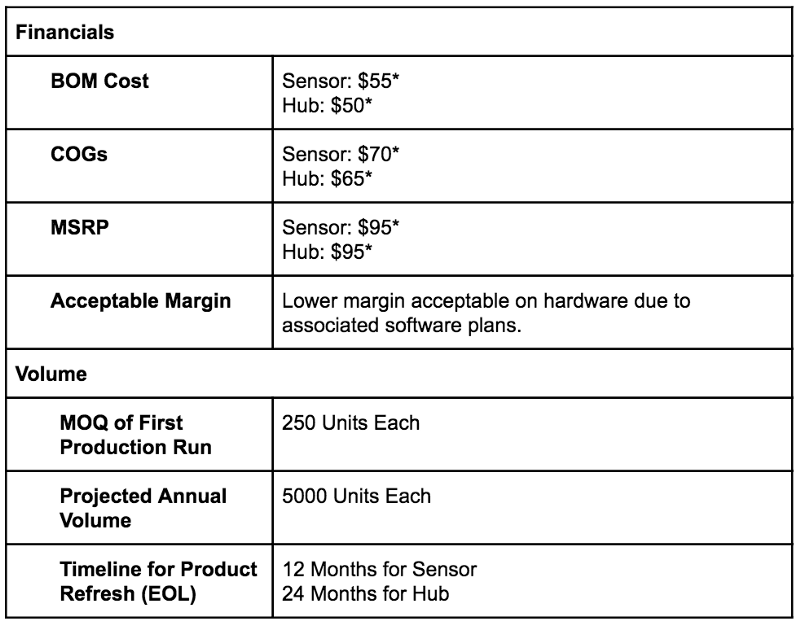

Financial

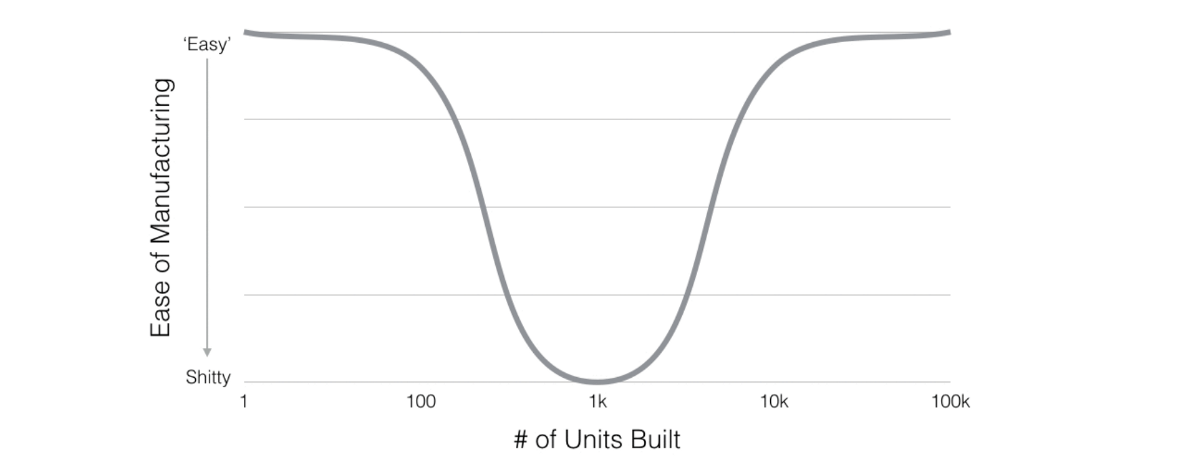

Hardware startups often have the difficult task of ramping up production with low initial volumes and relatively little capital.

Set expectations early about how much you think your customers will pay, how much it will cost to manufacture and ship your product, and how many you’ll have to make and sell to earn a profit.

For meanings behind some of the above acronyms and how to calculate the associated values, check our post on hardware jargon. Keep in mind that your sales price may need to be 2–5x your manufacturing cost, depending on how your business will generate revenue.

Industrial Design

Design is a broadly used word. Here we are talking about the usability, aesthetics, and interactive elements of the device. Be as visual as possible using sketches and renderings.

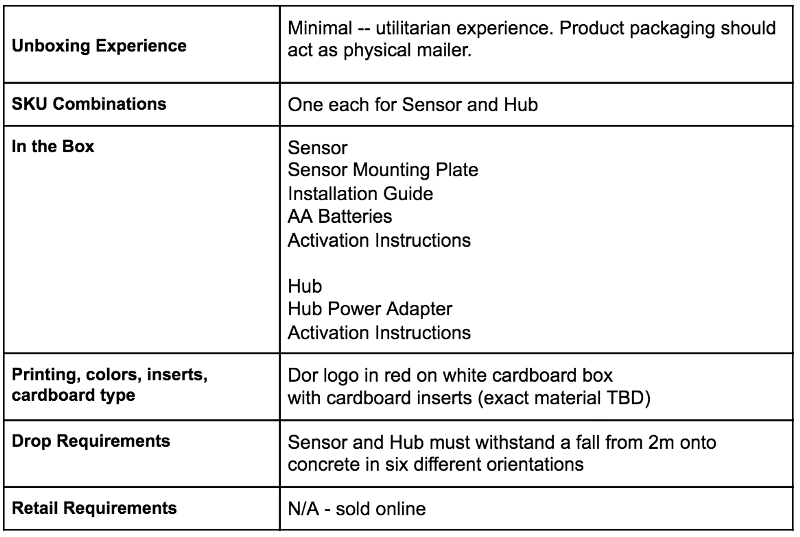

Packaging

Not to be overlooked, your product will need to be protected, presented, and likely shipped via a third party. Think about what needs to be included with your product and then about how you will protect it.

Depending on your product and your customer, this could be a simple, mostly-off-the-shelf paperboard box like Dor used or a custom solution that guides your customer through a curated experience.

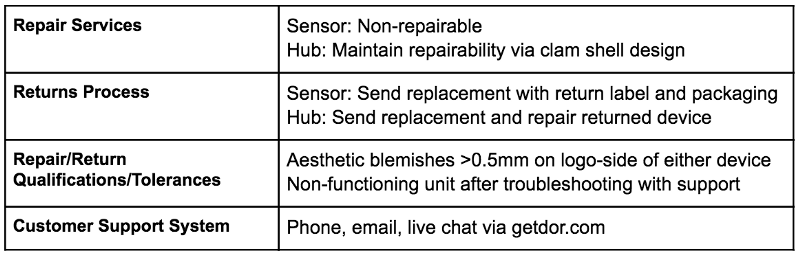

Serviceability

Not every product you sell will be perfect upon arrival to your customer, and others might break during use. How do you plan to define normal use, acceptable wear & tear, and your service policy?

If you plan to offer repair services, then you’ll need to design your product so that it can be disassembled. Dor’s sensor does not need to be opened by the customer, so we designed it with permanent heat stakes. Conversely, the plastics in the hub snap together and can be easily opened for repair.

Your Turn

The above are just a few samples to get you started. As you consider bringing your product to the market, spend some time defining the requirements before spending too much time on the hardware itself. Even if you can’t answer all the questions immediately, mark each unknown as TBD and make a plan to find a solution. Once you have a PRD, you’ll find it invaluable for aligning your team, seeing around corners, and constraining the design.

Get started here:

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.