It’s no secret that investors don’t like hardware businesses. Despite the eternal frustration of startup founders, investor distaste in physical product businesses is actually entirely logical. It’s nearly impossible to build a venture-scale business by selling dumb plastic parts at a 30% gross margin.

But the connected, vertically integrated hardware products of today are very different than their dumb counterparts of yesterday. The difference is simple yet profound: it enables hardware businesses to operate with financials that mimic their SaaS brethren. Somewhat surprisingly, the most notable example of this type of business model was pioneered by Keurig, a company few people think of as a hardware business. At Bolt, we believe this is one of the pillar business models of the next generation of hardware businesses, which is why our portfolio has a growing group of companies that follow this paradigm.

Background

The core Keurig system is quite simple: a machine (the brewer) and a proprietary system for packaging single-serve coffee (K-Cups). Like many great hardware inventions, the original Keurig machine was invented in a dorm room and grew slowly. The two founders built prototypes but struggled to gain mass-market adoption until 1996 when Green Mountain Coffee made a large strategic investment in Keurig. With a stroke of brilliance, they later acquired Keurig as a way to efficiently distribute higher margin coffee.

Keurig is one of most successful hardware companies of the past few decades. Except they’re not a hardware company. The vast majority of their revenue comes from coffee. In fact, 228M pounds of coffee per year, or more than 1.25 pounds for every coffee drinking adult in the US. Of the $4.7B in revenue in 2014, only $580M was from hardware sales. That’s less than 15%. Yet, without Keurig’s crucial piece of hardware, the booming business would likely cease to exist.

No more razors, no more blades

When discussing Keurig, nearly every single person will inevitably bring up the famed “razors and blades” business model pioneered by Gillette. The general gist is: sell a cheap “freebie” product (a razor) that requires continuous and high-margin replenishment to function (the blades). This is why a razor with a blade costs $7 but each blade after that costs $4 and why an inkjet printer costs $60 but each set of ink costs $40 or more.

Keurig is profoundly psychologically different from razors and blades.

Nearly everyone buying “replacements” has a negative association with these purchases. Think of your emotion the last time you purchased a set of ink cartridges. Unless you have a weird obsession with ink, I’ll bet it was a feeling of frustration and being ripped off. I imagine a used car salesmen with slicked-back hair trying to convince me I should buy two sets “just in case I run out.” Yuck.

Keurig on the other hand is always a positive buying experience. This primarily comes from the simple fact that you’re not buying replacements, you’re buying the thing you actually want to consume; the brewer is just a mechanism for delivery.

To Keurig or not to Keurig

Some might think there’s a fine line between Keurig-like business models and razor-like business models. Here are a few examples to test the boundary:

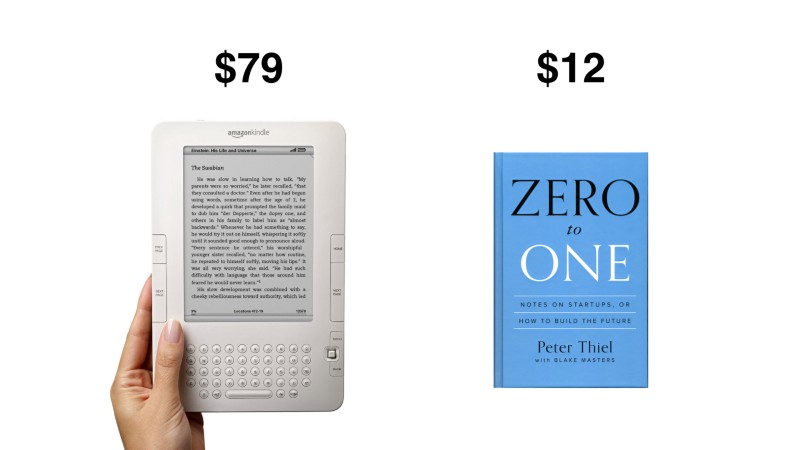

When you open the box for a Kindle, you’re excited to own a new piece of technology. But the real magic of the product experience comes when you purchase and read your first book. The device melts away from the experience and becomes an invisible facilitator for the act of reading.

- Verdict: Keurig for books (not razors and blades)

- Cost of consumable: 15% of device

The Brita water filtration system starts off as a complete product, but over time the filter wears out requiring you to replace it in order to get back to peak performance. Buying replacement filters, which are nearly half the cost of a full Brita system, feels like a nuisance.

- Verdict: Razors and blades

- Cost of consumable: 40% of device

Like the Kindle, game consoles aren’t very useful on their own. This is completely acceptable to consumers as the entire psychological experience of using a game console hinges on the games themselves, rather than the delivery system (the console).

- Verdict: Keurig for games

- Cost of consumable: 12% of device

Cost

A curious pattern emerges when looking at the handful of products on the market that follow these two business models. The relative cost of Keurig-like consumables to Keurig machines is much lower than the cost of razor blades to razors.

- Keurig cost of consumable: 1% of device

- Razor cost of consumable: 57% of device

In addition to the focus of the product (as discussed above), the price difference drives the negative psychological associations consumers have with razors-and-blades business models.

Why it matters

So who really cares? Plenty of companies have built big businesses by selling hardware at a 30% gross margin. Why can’t you just run a Kickstarter and sell a ton of units through Best Buy when to scale up? You can, you’re just entering into a game of diminishing returns with an extremely slim chance of winning in the long-run (check out this post for more detail).

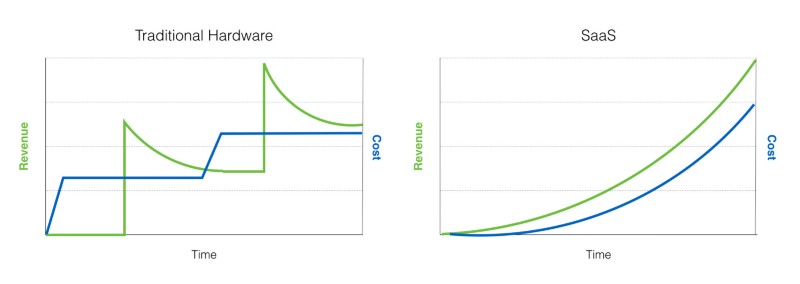

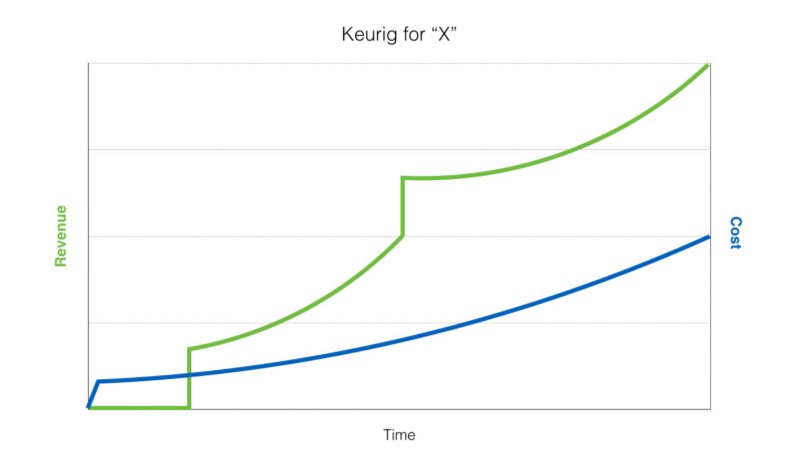

Recurring revenue matters because it fundamentally changes your business. There are good reasons investors are averse to hardware but love software. One of the leading reasons revolves around future revenue. Investors pay huge premiums to own stock in companies betting on the likelihood that future revenue will be drastically larger than current revenue. If you’re in a traditional hardware business, future revenue is confined to cyclic product sales. This roughly means you get one shot at revenue with each customer per product development cycle: each sale must be painfully acquired by building a new product every 18 months or so.

The Keurig model combines the best of both worlds: hardware-like customer acquisition and software-like recurring revenue.

Customer acquisition costs are often lower in hardware than in many SaaS businesses. This fundamentally comes from the psychological comfort we humans have from spending money on hardware ($120 for a coffee machine without thinking to hard) vs software ($120 for SaaS products is a difficult decision that very few average consumers make). For the inevitable customer acquisition cost that businesses do wind up paying, hardware companies recover that cost very quickly (usually in a few months at the point of sale) vs SaaS businesses (usually a year or more amortized over the usage of the product/service). Check out this post for more detail.

This is where the brilliance of the Keurig model shines. The initial sale of a $120 Keurig brewer isn’t that difficult or costly. Keurig doesn’t spend a lot on marketing or advertising and the product isn’t complex to manufacture or service. In my rough estimation, the BOM for a brewer is around $40, giving Keurig about a 25% gross margin on the product. Time from PO to FOB is likely less than 2 months, yet high-margin K-cup sales start immediately and continue for years. Keurig spends less than $0.015 on each K-cup and charges 100% more per unit than bagged, ground coffee. Yet few people complain about this cost.

For X

There aren’t too many businesses that are built around this model, but there will be.

In the past year, Bolt has made investments in Kuvée, Petnet, and Sutro (with a few more in the works), all of which follow the Keurig business model. Make no mistake: these products and businesses are exceptionally hard to build. Not only are you building hardware, firmware, back-end, front-end, mobile, operations, sales, and marketing functions, you’re adding necessarily highly-efficient, vertically integrated distribution system. Not a walk in park by any stretch of the imagination.

Our bet is once these businesses are built, they’re next to impossible to dislodge and their customers become devoted to their products and consumables.

Ben Einstein was one of the founders of Bolt. You can find him on LinkedIn.

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.