This is Part 3 of a three part series. Check out Part 1: Founders and Culture and Part 2: Contributors and Product if you missed them.

A startup is a machine that attracts, supports, and enables large numbers of people with different motivations (the solar system, remember?). One of the key differentiators between decent CEOs and excellent CEOs is their ability to design for the future of the company in the face of immediate pressing needs.

Designing the future of your startup has many components, but one of the most challenging is the so-called “organization design” or the reporting structure of the humans that work full-time with you. As your company grows, the solar system of people gets large and complex. Without strong organizational design, this network can become a liability rather than a resource.

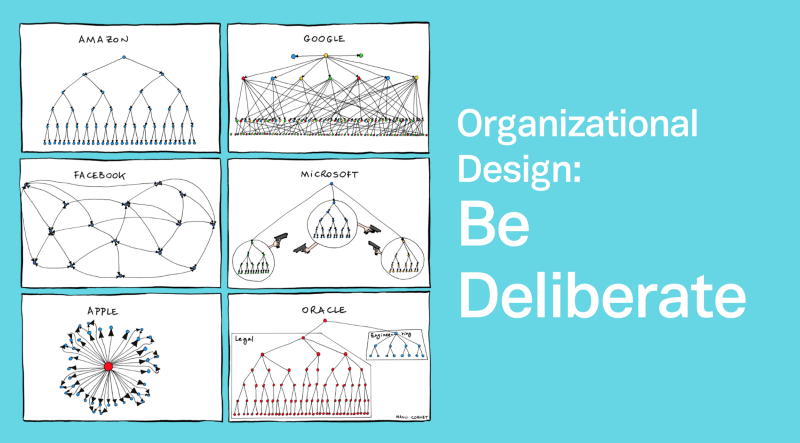

I love Manu Cornet’s satirical interpretation of some of the best-known tech companies and their organization designs. Be deliberate about your your company structure to maximize how team’s power.

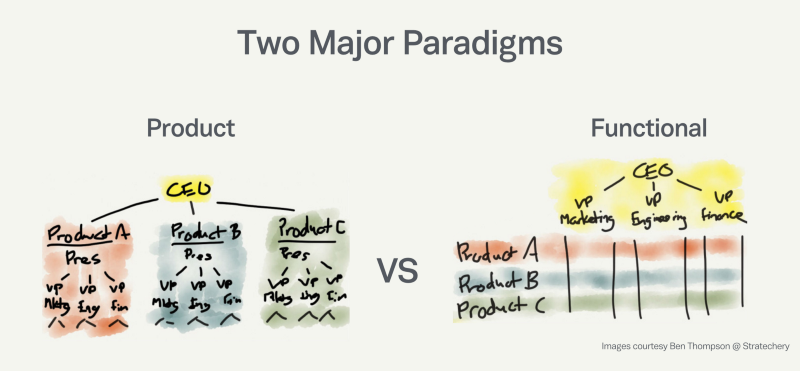

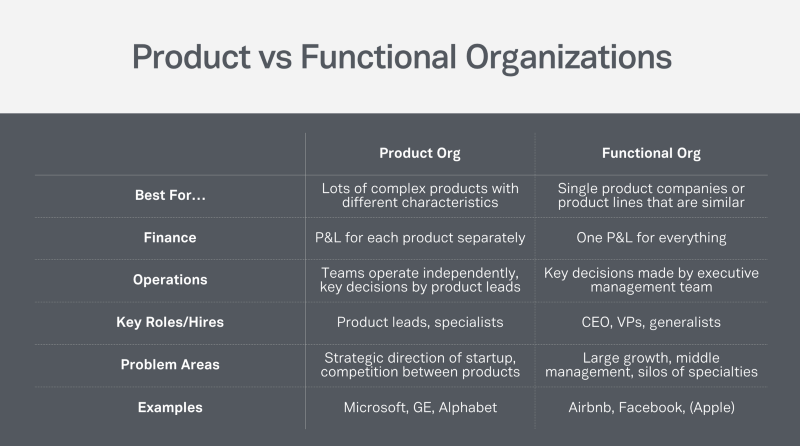

There are two major paradigms in organizational design: product organizations and functional organizations. Product orgs tend to be best for companies with lots of diverse products and product lines (such as Cisco or DJI) whereas functional orgs tend to be optimized for companies with a single product or platform (such as Juicero or Dropcam).

Deciding which company “you’ll be when you grow up” can be both frustrating and greatly illuminating to many people around you (including your investors). Take a quick look at the framework above to determine what kind of organizational design best fits your company and product(s).

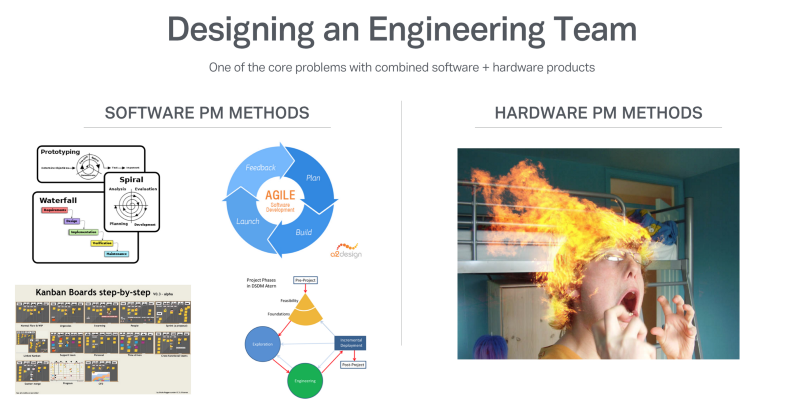

One of the constant debates in the hardware startup world is how to structure the engineering portion of your team when you have both software and hardware to develop. There are many tools and frameworks software engineering managers use to run their organizations: agile, waterfall, Kanban, etc. But when it comes to the hardware development process, most startups have their hair on fire just trying to ship something basic that works. This makes it all the more important to design your hardware engineering organization purposefully.

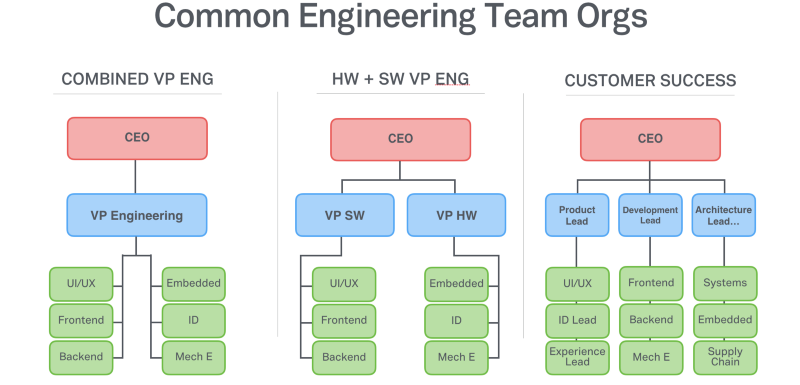

There are three common types of hardware/software engineering teams:

- Combined — The most common structure is a team lead by a single VP Engineering who manages both hardware and software. If you can find a stellar person with the ability and experience to do both, this is an excellent option. However, truly great VP engineering candidates for this role are very hard to find making this the most difficult structure to execute well on.

- Split Hardware and Software — Because software and hardware have such different time constants, team requirements, and management styles, it works well to have one VP who understands software management and one VP who understands hardware management. The trick is getting them to work collaboratively; if you decide to go this route (as many companies are starting to) the interpersonal dynamic between these leaders is critical to success.

- Customer Success — Organizing your engineering/product team around the customer involves separating different aspects of your product into separate teams along the perspective of the customer rather than technologies. Having a product team (which focuses on the things the customer touches), development team (which focuses on implementation of the design), and architecture team (which focuses on longer-term, strategic design issues) can help simplify urgency and task management. While there aren’t many companies doing this yet, there is a new trend that I suspect will become more common in the next decade.

Early on, the founding team and engineers need to communicate directly with customers about their experience gets imbued in the company consciousness. While this is critical in the beginning, it turns our most engineers aren’t very good at communicating with customers. Once you ship your first product, hiring a Product Manager to be the interface between the engineering/design team and your customers is incredibly valuable. Many companies do this far too late and wish they had done it sooner. My advice- do it as soon as you can afford to.

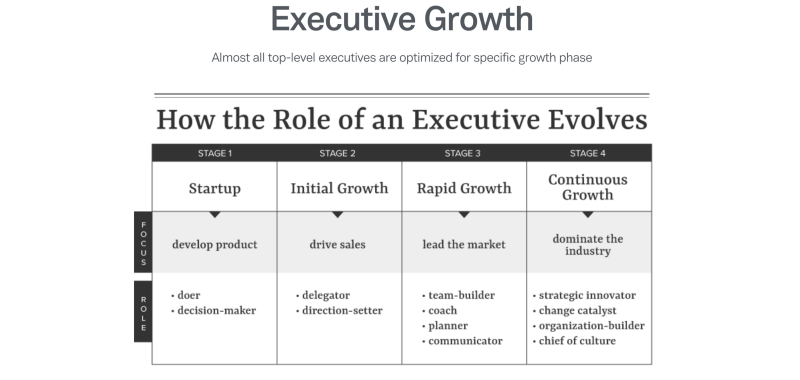

As a startups grows from a few people working on a single product to a complex organization supporting multiple products and customer segments, the requirements for successful leadership changed. This is not always the case, but it is not uncommon for people who have performed exceptionally in the early days of a company to no longer be the right fit to lead as the company scales. This isn’t a failing of these individuals, rather a natural side effect of company evolution and growth. Being emotionally prepared to facilitate this transition, both for those you have hired and for yourself as a founder, can help prevent pain further down the road.

Efficient and fair evaluation of employees is critical to building a team continually improved.

- Assessment — getting into the habit of assessing employees and managers is incredibly powerful. Many companies have moved away from annual reviews in favor of quarterly or monthly feedback sessions, often incorporating bi-directional feedback (sometimes called 360 degree feedback).

- Feedback — communicating assessments to employees, managers, and cofounders breeds healthy teams. Giving feedback is hard to do well and usually takes a healthy dose of honesty. As cheesy as it sounds, the good ‘ole “compliment sandwich” is a very useful tool for constructive criticism. I’ve also found it helpful to separate “performance” feedback from any conversations about compensation.

- Nurture High Performers — it’s common for a few powerful performers to stand above the rest. Keeping high-performers excited about the future of your company will help you retain them. Oftentimes these high performers will also also help you attract other good people.

- Remove Low Performers — similarly, it often becomes clear that there are a few people on your team who are not performing the way you expected. Almost always, this is a bad situation for both the employee and the company. After giving direct feedback and allowing some time for the employee to improve their performance, it’s best to let them go if no change is made. This is one of the hardest things to do as a manager. Approach these conversations from a place of compassion.

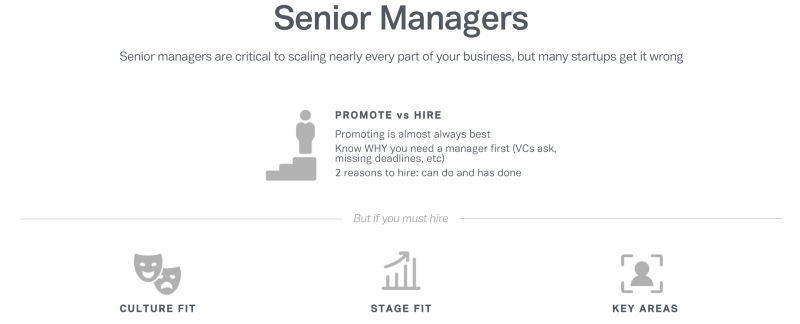

A large organization needs managers. Promoting individual contributors to become managers is almost always the preferred option, but there are many cases where this isn’t practical. Deciding when to hire a (usually expensive) manager can be a hard decision. An advisor of mine once gave me a valuable tip: either you’re hiring an outside manager for CAN DO (meaning something that you won’t be able to figure out on your own, like optical engineering) or HAS DONE (meaning something that you need experience to execute on, like industry sales experience).

Once you decide to hire an outside manager, these three areas of fit are particularly important to get right:

- Culture Fit — it’s very risky culturally to bring a new person into an existing group of high-performing contributors. Hiring managers who are overly senior can create a cultural imbalance where contributors feel like they’re getting “adult supervision.” Making sure a new manager is comfortable with the tools, best practices, existing work cadence, and current management style of the team is critical to a healthy transition.

- Stage Fit — To reduce turn over, make sure the manager you’re hiring is suitable for both the current stage and the immediate next stage of your company. An awareness of which of the four stages you’re in will lend clarity to selection.

- Key Areas — certain disciplines within the organization tend to be more common for outside managers. These are manufacturing/operations, quality control, finance/CFO, and retail/distribution/sales.

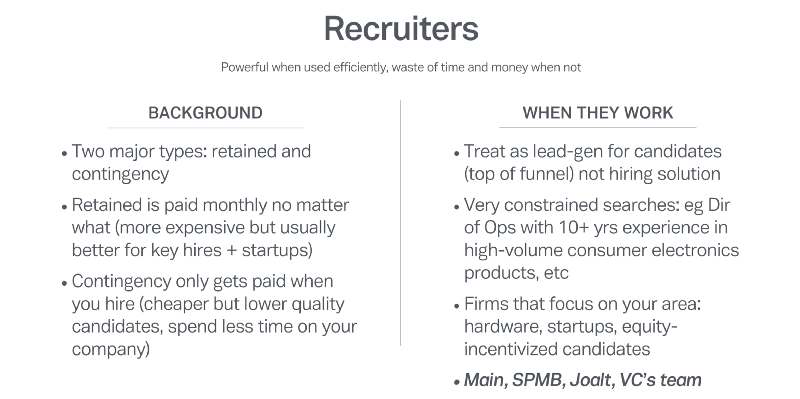

Finding strong outside manager candidates can be wildly difficult. For key managerial positions, it can make sense to hire a recruiting firm. Ensure you hire the right kind:

- Retained — by far the more expensive (but better option). Retained search firms are paid a fixed monthly fee whether or not you hire their leads. These firms tend to be much more expensive but provide higher quality candidates.

- Contingency — is only paid when you hire a lead they send to you. Typically they take a “shotgun” approach, sending many candidates your way in the hopes you hire one and they get paid. While far cheaper, quality tends to be much lower.

With both options, it’s important to recognize the startup is responsible for hiring the right person, and as such, you should only treat the output from either type of firm as a lean generation mechanism, not a hiring solution.

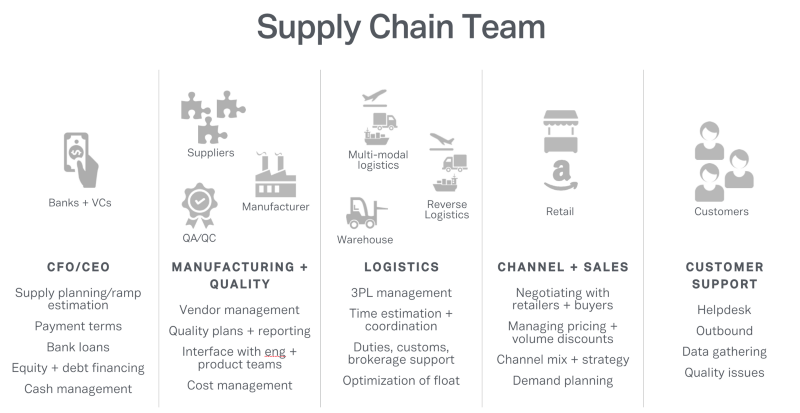

As hardware companies scale, they often ignore two essential teams: supply chain and cash. These teams are usually complex groups of full-time employees, part-time employees, consultants, consultancies, manufacturers, lawyers, accountants, and service providers. Recognizing their value is paramount to success.

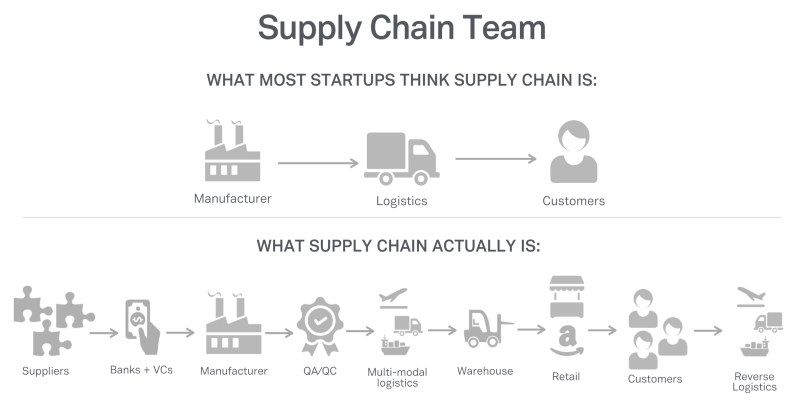

Many startups have the perception that their supply chain is simple: a contract manufacturer makes stuff that is moved around by a logistics company to your end-customers. On the 80+ products I’ve worked on in my life, this has never once been the case.

In reality, your supply chain is a complex web of people with different incentives and business models. Treating each of them with respect (as they control your cost, quality, and schedule) will make everyone’s life easier. One tool I’ve seen hardware startups wield very effectively is a simple rule:

Every single person/company in your supply chain gets pitched on your company’s vision just like a VC does.

This ensures everyone from the “lauded” venture capitalists to the “lowly” logistics providers treat your product with care and attention, situating themselves as critical to the future of your company.

As a point of reference, the above chart shows the various major pieces in the supply chain team and what each is typically responsible for.

Similarly, understanding how important cash management is to the vitality of your startup will help you incentivize the right people and make it easier to survive. Focus on three things when managing cash:

- One Goal — when it comes to cash, your job is simple: don’t run out! In some ways, this is the primary job of the CEO. In order to do this, you must manage your inputs (venture capital, banks, debt, revenue) with outputs (salaries, inventory, tooling). If you can solve that equation, you’ll be successful!

- Reduce Complexity — one of the easiest ways to win at managing cash is to simplify your life. Things like lowering SKU count, selling to fewer countries, and managing returns will make your life dramatically easier and your likelihood to manage cash much higher.

- Team — just like the supply chain team, there are many people on your cash team that you may not think of: CFO, accounting firm, CMs, suppliers, VCs/angels (that know hardware especially), banking, debt providers, etc. Make sure to keep them all incentivized for the long-term success of your business.

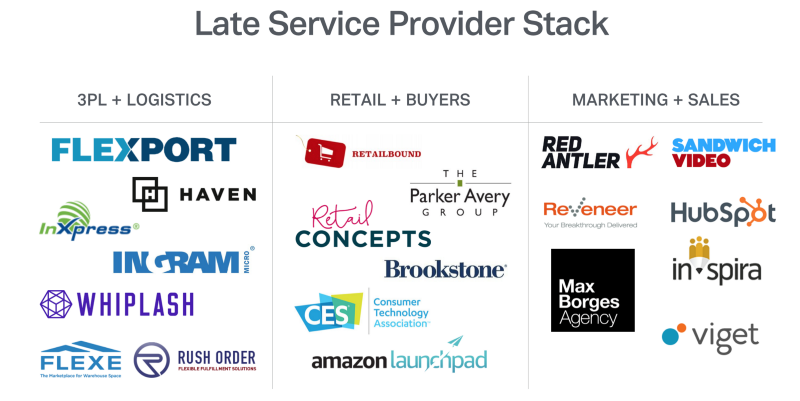

There are three major categories of service providers that tend to be helpful for later-stage startups when thinking about logistics, retail, and marketing/sales. The companies above are commonly used by our portfolio and the greater hardware startup community.

Most importantly of all, don’t forget to surround yourself with people that inspire and motivate you every day! Having people you love as a core part part of your day-to-day work will make every experience better.

That concludes this three part series on building teams for hardware startups. Check out Part 1: Founders and Culture and Part 2: Contributors and Product if you missed them.

Ben Einstein was one of the founders of Bolt. You can find him on LinkedIn.

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.