Absolutely. But it’s tricky.

There’s one thing investors look for that’s paramount to every other: traction. You can build a great team, be in a large/exciting market, and have an exceptional vision for changing the world but investors can always disagree.

It’s next to impossible for investors to say ‘no’ when you show traction.

The ability to show early traction is the key enabler of the proliferation of SaaS businesses. With minimal cost and time, a few kids in a dorm room can demonstrate the potential to build a product that millions (or even billions) of people want to use. A sea of terms have developed to describe SaaS traction: MAU, ARPU, DAU, NC, K-factor, churn, CTM, IT, TC, CR, MRR, LTV, CPA/CAC, CTA, NPS, ACV, etc. Even if the number of users is relatively small (in the thousands), SaaS startups can generate objective data that qualifies their product/market fit quite well.

But objective data for hardware startups that have yet to ship a product is much harder to gather.

Hardware startups can demonstrate traction just as well as SaaS businesses. Crowdfunding isn’t the only tool you have.

But it requires a bit of creativity. Every product and market is different so generic metrics may not be precise enough. Here are a few tips to make the process easier.

Your mission: find 30 perfect customers

A big mistake hardware startups make is thinking they need huge numbers of users before they can gauge product/market fit. While this is obviously preferable, getting data from thousands of users when a hardware product is involved usually requires full-scale production (which defeats the whole purpose of gathering metrics). Over years of developing hardware products, I’ve found feedback from ~30 well-qualified potential customers to be shockingly accurate at predicting long-term market adoption. Key insights only come when A) you know how to measure your product experience and B) the people you’re asking for feedback are the perfect target customers. Both of these are hard to do. I hope these 3 steps helps make both of them easier.

1. Understand your target users

Many hardware startups that we meet are shockingly oblivious about who their own future customers are. Do yourself and your investors a favor by being extremely rigorous about your very earliest customers:

- Good consumer startups understand (and have data) how to characterize their customers in detail. They understand the psychological and demographic characteristics their earliest adopters (commonly called the innovators or thought leaders) will have. They’ve found which DMA (designated marketing area) these users are most likely to live in and have done work to prove that people in these DMAs are likely to provide positive feedback after using the product. They know how many people there are in the country/world that that fit this profile and how best to reach them. They’ve made sound assumptions on how to grow their customer base from innovators to early adopters.

- Good B2B/enterprise startups understand their market structure from the inside (usually by talking to people that were major stakeholders in their industry). They have a good idea of sales cycle timelines, who makes purchasing decisions within different types of organizations, and how much money the decision makers have to spend. They’ve networked aggressively with both C-level executives and people on the ground at potential customers. Some companies even go as far as getting signed letters of intent describing that a given customer is willing to purchase your product.

Understanding how to quantify your customers is the bedrock for demonstrating traction.

While going through the process of identifying/quantifying target users, startups that obsess over finding a small number of perfectly qualified users always outperform ones with large numbers of vaguely potential users. Be exceptionally selective with your first customers and you will be rewarded with off-the-charts positive feedback.

2. Measuring user engagement

After you’ve identified a good group of target customers, your next step is to assess whether or not they respond well to your product. This usually requires building a solid functional prototype that users can take out of a box and interact with. Focus on a minimal feature set that’s strong (rather than a half-baked, but large feature set).

The best measure of traction comes from people who have USED your product. Fake ‘buy now’ buttons and crowdfunding campaigns give feedback on how many people would pay to solve a problem, not whether your product actually solves it.

Here are a few tools you can use to demonstrate traction during this phase:

- Subjective feedback

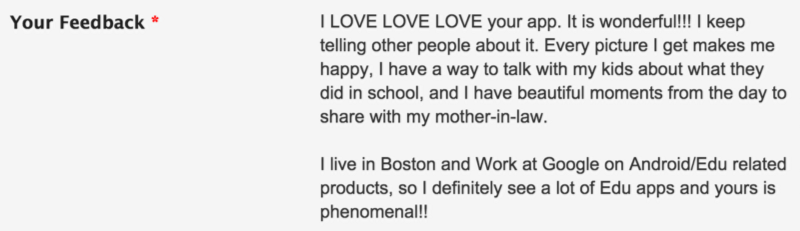

A long-standing pillar of the product design process is conducting “exit interviews” (confusingly often called customer/user interviews) where a prospective customer interacts with a prototype of a product and answers a series of questions. It takes years to do exit interviews well without major bias but is a good data point to collect regardless of objectivity. While written feedback is most common, recording video testimonials can be far more powerful. One of the main drivers of us investing in Kaymbu was the early feedback they had from teachers and parents:

- Net promoter score (NPS)

NPS is a fantastic tool in your arsenal when it comes to measuring feedback objectively. NPS simply asks the question “On a scale of 0–10, how likely are you to recommend this product to a friend?” It turns out, the more likely someone is to recommend a product they more likely they are to buy it. NPS can only be accurately tracked once someone has used your product, but its simplicity removes a large portion of bias implicit in subjective feedback.

- Emotional analysis

Ever since I read John Gottman’s famous study using facial analysis to predict divorce rates, I’ve been fascinated by subtle clues humans unknowingly display that express how we feel. Most product designers are well-versed in asking explicit questions and reporting on the explicit answers given by users. But this often ignores the most important feedback we’re given: the emotional one. Unbeknownst to most founders, emotion trumps rationality when it comes to making purchasing decisions. When doing product exit interviews, recording basic emotional characteristics on a 1–5 scale can be super helpful at demonstrating how early users feel about your product.

- Community growth

While this doesn’t work for all products/markets, the growth of the community around a product and how fellow users interact with each other can be a great predictor of success in the broader market. I remember noticing this the first time I saw Bre talk to people around the first MakerBot booth at MakerFaire. It was clear MakerBot would have a very powerful community when listening to dads talk to their kids and even other kids talk to each other while standing around the booth. Ways you can demonstrate the community growing around your product (and of course why that happens) is roughly equivalent to a K-factor in SaaS products. - Vanity metrics

There are a host of metrics that startups can use to show that someone somewhere believes in their product. While I’m not a fan of most of these metrics because they don’t address user interaction, things like the number of retail stores interested can sometimes be enlightening.

3. The culture of traction

Startups that think traction is shown on a single slide in a deck that gets updated once in awhile misunderstand how crucial a “culture of traction” is to an early stage startup. Our friends at Y Combinator ask startups to track growth weekly, and we agree.

Tracking SaaS-type metrics for an early stage hardware company is challenging, so picking one or two metrics to track continuously is usually the best bet. The most diligent founders force themselves to gather both objective and subjective feedback from X customers per week (often 10 to 20) in the search for those perfect customers. Most commonly, we see NPS and some subjective feedback reporting but mileage may vary depending on what market you’re in.

Once you’ve established a culture of traction, communicating this to investors can impact your financing (valuation, quality of investors, terms, etc) more than any other set of metrics. Early investors don’t actually need troves of hard data, they need a rosy story painted about your customers that’s backed up with enough data to make it believable and exciting. Crafting this story well can be worth millions of dollars.

Ben Einstein was one of the founders of Bolt. You can find him on LinkedIn.

Bolt invests at the intersection of the digital and physical world.